A Re-Evaluation of Past to Present-Day Use of the Blissful Neuronal Nutraceutical “Cannabis”

A B S T R A C T

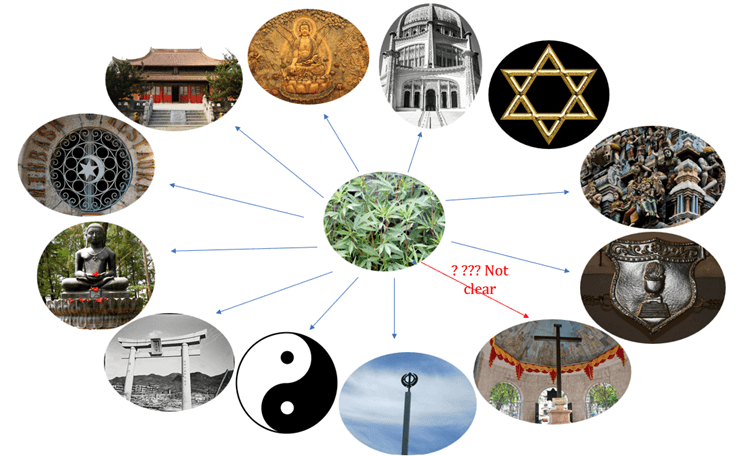

The chronological events associated with cannabis utilization are viewed perceptively as matters/issues that happened from the period “before Christ” (BC) or “anno domini” (AD, “in the year of our Lord”) to the present time. Cannabis is one of the oldest natural products known to humanity worldwide and has been used by various civilizations, cultures, and religions before the birth of Christ. Interestingly, it is used to date and has the potential for future usage for centuries to come. Currently, the major religions around the world are Christianity, Islamism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Taoism, Judaism, Confucianism, Bahá'í, Shinto, Jainism, and Zoroastrianism, with their precepts regarding the use of cannabis products. Similarly, the most noted ancient civilizations, including the Incan Civilization, Aztec Civilization, Roman Civilization, Ancient Greek Civilization, Chinese Civilization, Mayan Civilization, Ancient Egyptian Civilization, Indus Valley Civilization, and Mesopotamian Civilization, have reported cannabis use. This review discusses cannabis in various civilizations and religions from the past to the present day.

Keywords

Cannabis, history, indication, neuronal nutraceutical, traditions

Introduction

Civilization fundamentally refers to the progress made by humans to live in peace, harmony, composition, and collectively in societies or communities. Ancient civilization refers exclusively to the original and the earliest established and stable societies or communities, which became the foundation for the subsequent empires, countries, and continents. Historically, the most remarkable civilizations are the Incan, Aztec, Roman, Ancient Greek, Chinese, Mayan, Ancient Egyptian, Indus Valley, and Mesopotamian Civilizations. However, religion is characterized as a system of faith or worship and a spiritual experience where a human believes in a higher power (Supernatural things or Gods). Christianity (approximately 33-34% of the world’s population) is the most prevalent religion presently, followed by the Islamic religion (about 23-24% of the world’s population). The other major religions include Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Taoism, Judaism, Confucianism, Baha’i, Shinto, Jainism, and Zoroastrianism. There are quite a few distinctive and diverse religions globally with specific ritual processes and natural products in their daily lives. Since time immemorial, humans have used natural products (specifically botanicals and herbs) as food, medicines, recreational substances, crops, and feed for their livestock. During historical evolutions, various civilizations and religions have discovered, cultivated, experimented, and documented the use and value of natural products. They also passed the knowledge of these botanicals to their future generations. Throughout history to today, the use and consumption of cannabis have been an integral part of various cultures, civilizations, and religions. Cannabis is one of the oldest botanicals known to humans.

Historically, Chinese medicines are derived from botanicals (arboreous and herbaceous), animals, microbes, and minerals. Pan-p’o village (also referred to as Banpo, 4000 BC) is an archeological site located in the Yellow River Valley, China, with remnants of numerous perfectly planned structured Neolithic settlements where there is evidence of several uses of several botanicals, including Cannabis. The Sheng-nung Pen-ts'ao Ching and Pen-ts'ao Kang-mu (oldest Chinese Materia medica, compilations of herbal drugs, 2737 BC) have references regarding Cannabis [1]. Correspondingly, in the ancient Indian medical system, “Ayurveda” (Ayu = life, Veda = Science, 2000BC), there is significant literature on the ritualistic/ceremonial and medicinal use of Cannabis. Ayurveda, a traditional Hinduism-centered approach to human remedy, has a philosophical core based on the concept of diet, botanicals, and yoga for a better way of life. In Egypt (1550 BC to 1213 BC), there is evidence for the use of Cannabis in Ebers Papyrus (synonym = Papyrus Ebers, papyrus = thick writing surface). Later, there is literature on the benefits of Cannabis in other parts of the world, such as Greece, Rome, Persia, Spain, the Americas, Africa, and Asia. In the early 19th century, many countries adopted legislation to control the cultivation and consumption of Cannabis (Tables 1 & 2).

Table 1: Chronology and history of cannabis utilization.

|

Year |

Location |

Information on Cannabis Utilization |

|

4000 BC 2900 BC 2737 BC |

China

|

Pan-p’o village (Banpo) Fu His (Chinese emperor) Sheng-nung Pen-ts'ao Ching / Kang-mu, Materia

medica |

|

2000 BC |

India |

Ayurveda (Indian /Hindu Medical System) |

|

1550 BC 1450 BC 1213 BC |

Egypt |

Ebers Papyrus Exodus Ramesses II (Pharaoh) |

|

900 BC |

Northern Iraq, Southeastern Turkey |

Assyrians |

|

700 BC |

Persia |

Venidad (volume of the Zend-Avesta) |

|

450-200 BC |

Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey |

Greco-Roman |

|

207 AD |

China |

Hua T’o (Surgeon) |

|

1025 |

Persia |

Avicenna (Medical writer) |

|

1300 |

India to Eastern Africa |

Arab traders |

|

1500 |

Spain to Americas |

Spanish Conquest |

|

1798 |

France |

Napoleon Bonaparte |

|

1839 |

Britain |

William O’Shaughnessy (Medicinal Property) |

|

1900 |

|

Medical Cannabis (OTC product) |

|

1914 |

United States of America |

Harrison Act (Cannabis prescription) |

|

1937 |

United States of America |

Marihuana Tax Act |

|

1964 |

Israel |

Discovery of THC (Raphael Mechoulal) |

|

1970 |

United States of America |

Classified as Schedule 1 Drug |

|

1988 |

United States of America |

Discovery of cannabinoid Receptors (Allyn

Howlett) |

|

1900– Till date |

Around the World |

Legalization of Cannabis |

OTC:

Over The Counter product of cannabis.

Table 2: Important features of religious beliefs Cannabis and

use.

|

Major Religion |

Spiritual |

Recreational |

Medicinal |

Commercial |

|

Christianity |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

|

Islam |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Hinduism |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Bahá'í |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Buddhism |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Confucianism |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

|

Jainism |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Judaism |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

|

Shinto |

Yes |

|

|

|

|

Sikhism |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Taoism |

Yes |

No |

Not Clear |

No |

|

Zoroastrianism |

Yes |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Excitingly, in the last two decades, this natural product has been transformed drastically, redesigned (bioengineered, new strains), and modernized for the current consumption. Thus, the uninterrupted and continual human fascination with the recreational and beneficial effects of cannabis has led to the significantly enhanced modern-day use of cannabis as a medicinal and commercial natural product. The medicinal, recreational, and commercial benefits of cannabis in a particular society have been constantly passed on to the subsequent generations, leading to the current traditional spiritual, household, therapeutic and commercial uses. Therefore, this review explores the “cannabis custom” in various civilizations and religions.

Religious Belief and Opinions on Cannabis

I Christianity and Cannabis

During the initial period or start of Christianity as a religion, cannabis was used in Indian, Chinese, Assyrians, Persians, and Middle Eastern cultures for medicinal and commercial purposes [2-5]. There appear to be no specific or direct references to cannabis in the Bible. However, some theological scholars propose that cannabis does appear quite a few times, in the Old and New Testaments, but has been mistranslated, perhaps intentionally. The proposed indirect cannabis-associated references in the Bible imply a sense of respect for the potency of cannabis. From the Holy oil of Moses to the healing miracles of Jesus, it is proposed that cannabis is camouflaged in the best-known story versions of some of the Jewish and Christian Scriptures. Historians interpret the words of Genesis 1:29 to suggest that cannabis-containing plants were created for humans by the Lord because they are innately healthy like other botanicals. In another verse, God tells Adam that “Every plant yielding seed that is on the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit, you shall have them for food.” However, some theologians have argued that this verse should not be interpreted literally since there are numerous botanicals that are lethal for individual consumption. Also, numerous spiritual leaders of the Christian faith are not persuaded that this biblical passage expresses consent for smoking cannabis products.

In the Song of Songs 4:14, King Solomon romantically portrays his new wife by matching her qualities to an assortment of desirable plants, fruits, oils, and fragrant calamus, which some theologians assume to be a mistranslation of cannabis. Similarly, it has been conjectured that the harvest referenced in Isaiah 18:4-5 and later in Isaiah 43:24 may refer to the cannabis plant. At one point in the Bible, the Israelis are rebuked for their hypocritical worship habits because Israelites did not procure “sweet cane” for offering to his Almighty. In this holy scripture, the “sweet cane” is the Holy anointing oil ingredient, and several scholars suggest this may have been considered cannabis. Interestingly, in Jeremiah 6:20, God conveys discontent with the material sacrifices offered by his devotees as an offering to atone for their sins. “Incense from Sheba and the sweet cane from a far country” is exclusively cited as a deplorable offering in this situation. Furthermore, the historians believed that incense and sweet cane in this holy verse might have been cannabis.

Ezekiel 34:29 refers to a “plant of renown” that is considered to be referred to as hemp with few interpretations. Nevertheless, there is considerable disagreement regarding this passage because it might be referring to a fruitful land for planting, not a particular plant. Remarkably, the greatest presumed cannabis quotations in the Old Testament are in the book of Exodus. Moses begins speaking with Lord after examining a botanical (bush) that he observes to be on fire but not being consumed by the fire (Exodus 3:2-5). Immediately, God directs Moses to bring the Israelites out of Egypt, and when Moses accomplishes this feat, God continues to visit him providing divine guidance. Some have speculated that this communion between God and Moses took place under the influence of cannabis. God is even described throughout Exodus as making His earthly appearances in clouds of smoke. In Exodus 19:9, God tells Moses, “I will come to you in a dense cloud so that the people will hear me speaking with you and will always put their trust in you.” In Exodus 30:1-9, Moses was instructed by God to set up an altar inside his tent for the sole purpose of burning incense which may have been cannabis. When the cloud of smoke could be observed at the door, his followers would assemble outside the tent in prayer.

In the scriptures, Jesus is reported to anoint common people with His healing oil. As described in Mark 6:13, “They cast out many devils and anointed with oil many that were sick and healed them.” Matthew 4:24 goes on to say: “News about Him spread all over Syria, and people brought to Him all who were ill with various diseases, those suffering severe pain, the demon-possessed, those having seizures, and the paralyzed; and he healed them. Biblically, Jesus has been praised as a “miracle worker” for treating or healing several pathological conditions. The various pathological conditions are dermatological disorders (leprosy, dermatitis, eczema, and psoriasis) and musculoskeletal disorders (rheumatism, multiple sclerosis). About the musculoskeletal disorders, Jesus is referred to as “the straightener of the crooked limbs” in the Acts of Thomas. Furthermore, Jesus has also cured ophthalmic / Eye disease (glaucoma), central nervous system disease (epilepsy, demonic possession), endocrinological diseases related to menstruation (dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia), and uterine hemorrhage related to childbirth. Intriguingly in recent years, all the pathological conditions listed above have been shown to therapeutically respond effectively to cannabis treatment.

To recap, Christianity is the most prevalent global religion and does not have any direct historical coupled with specific literature and scripts on the consumption or commercial aspects of cannabis. However, there are numerous assumptions regarding the indirect mentioning of botanicals or cannabis in their holy scripture or other scholarly writings. In recent years, the leaders of Christianity and the place of worship have issued considerable caution and discouraged cannabis consumption but have not opposed the medical use of cannabis to treat human ailments. The Bible never outrightly condemns the use of cannabis. There were no laws against using cannabis in the Hebrew or ancient Christian texts. At the time the Bible was likely written, people in the Middle East were well aware of the existence, usefulness, and potentially intoxicating factors of cannabis-containing plants. The views of the many different denominations of Christianity on cannabis use are somewhat varied. Before assuming his position as leader of the Catholic Church, Pope Francis spoke out against recreational cannabis. In 2013 in Buenos Aires, he stated: “A liberalization of drug use will not achieve a reduction in the spread and influence of drug addiction.” Also, the catechism of the Catholic Church states that "The use of drugs inflicts very grave damage on health and life.” Except on strictly therapeutic grounds, their use is a grave offense in Catholicism. Most Protestant churches, including the Presbyterian, United Methodist, Church of Christ, and Episcopal Churches, have endorsed medical Marijuana but oppose recreation use. However, some segments of the Protestant church are against even medical use. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints has a general prohibition against intoxicating substances. In August 1915, the Latter-day Saints (LDS) Church banned cannabis by its members. In 2016, the church's leadership urged members to oppose the legalization of recreational cannabis use but supported efforts to legalize cannabidiol (CBD) in Utah.

II Islamism and Cannabis

Islamism is the second most prevalent religion in the world, following Christianity. Based on the Avestan hymns in the Gat-ha (holy scripture), Zoroastrian priests have grown and utilized ‘sacred plant cannabis preceding the Islamic era [6]. However, there is a lack of quotations or excerpts regarding cannabis in the holy Koran. Moreover, clerics have mentioned that there is no direct input by the Prophet Muhammad regarding this issue. Historically, cannabis has been traditionally used for Islamic spiritual rituals, religious performances, and curative purposes from the beginning of the Islamic era. In the Islamic nations or the Arabic norms, cannabis is popularly referred to by different names due to its wide utility. The various names are as follows: the herb of the immortal or the sacred herb (hashish Hum, homa, soum, sama, giyah-e javidan, giyah-e moqaddas, khadar (‘green’), kimiyah (‘alchemy’), qanaf (‘hemp’), zomord-e giyah-e (‘smerald herb), “grass,” bang (whole cannabis residue) [6-8]. However, cannabis as a plant, seed, or medication is generally referred to as charas, gol, jay, Marijuana, sabz, or shahdaneh (the royal seed) in the modern world. Hashish, dugh-e vahdat (drink of unity, form of yogurt) and hashish pipe (nafir-e vahdat, the trumpet of unity with God] has been preferred natural product or botanical-based product used for recreational purposes from the 13th century to till date by the Mongols, Sufi, Dervishes, Qalandars (Khorasan, Eastern Iran) and others.

The Islamic world (Islamic countries and specifically the Middle Eastern countries) has very rigorous and stringent laws of prohibition, mainly on sexual customs (premarital sex), social practices (gambling), and consumption of addictive substances (alcohol and narcotics) by individual Musalman. Narcotics, however, are hardly exceptional to Islamic societies and/or the Middle Eastern nations. The prohibition of narcotics has been a general feature of the 19th and 20th centuries, and strict laws are enforced for the use and/or possession of narcotics [7, 9-14]. Islamic civilizations have had protracted and spirited descriptions of deliberation around the values and vices of cannabis. Specifically, Islamic (mainly Persian and Arabic) scientists, intellectuals, researchers, historiographers, and composers/poets have assessed cannabis usage in their respective social milieu [15, 16]. Interestingly, cannabis was not merely a natural product of spiritual experience and unorthodox mysticism but had been mentioned in various Islamic medical literature, books, and pharmacopeia of several Islamic countries [7]. In the legal and strict spiritual area of drugs policy, the Islamic leaders, clerics, and the holy places have strictly condemned drug trafficking and banned it.

Furthermore, they have a death penalty law for people violating these laws. Interestingly Islamic clerics have approved and adopted several policies to solve the drug addiction issues and have endorsed the medical practices regarding methadone maintenance. To conclude, exposure of Cannabis to Islamism has occurred for a long time and currently Islamic countries implement an extremely rigorous prohibition [13, 17]. However, based on their belief of Koranic verse (al-kul maytah) and an accepted tradition (hadith-e raf, which emphasizes that outlawed actions are allowed during difficult times or emergency), cannabis has been allowed to be used for medicinal purposes. The Quran does not directly forbid cannabis. In 1378 Soudoun Sheikouni, the Emir of the Joneima in Arabia, prohibited cannabis, considered one of the world's first-attested cannabis bans [18]. Today there is a controversy among Muslim scholars about cannabis as some deemed it to be similar to the alcoholic drink Khamr and therefore believed it to be forbidden. However, some scholars, especially in Shia sects, consider cannabis to be permissible for medicinal use. Those scholars who consider cannabis forbidden refer to a hadith by the prophet Mohammed regarding alcoholic drinks, which states: “If much intoxicates, then even a little is haram (forbidden).” However, early Muslim scholars differentiated cannabis from alcohol, and despite restrictions on alcohol, cannabis use was prevalent in the Islamic world until the 18th century [16]. Today, cannabis is still consumed in many parts of the Islamic world, even sometimes in a religious context particularly within the Sufi mystic movement [19]. Also, some modern Islamic leaders state that medical cannabis, but not recreational, is permissible in Islam. Imam Mohammad Elahi in Dearborn Heights, Michigan, declared: “Obviously, smoking marijuana for fun is wrong. It should be permissible only if that is the only option in a medical condition prescribed by medical experts.”

III Hinduism and Cannabis

Vedas are the most primal Hindu sacred scriptures, and their existence may date back to roughly 1700 before the common era (BCE, the Late Bronze Age). The major Vedas are Rig Veda, Sama Veda, Yajur Veda, and Atharva Veda. Vedas consist of hymns, philosophy, and guidance in the Sanskrit language. Vedas primarily assist the priests with various holistic rituals. Historically, Vedas are thought to have been directly revealed to seers/clairvoyants amid the primary Aryans in the Indian sub-continent. This was mainly well-maintained by verbal and uttered custom. Similarly, Shruti is the highly sacred body of Hindu literature and is considered the consequence of celestial and heavenly disclosure. Shruti compositions are believed to have been passed on (by hearing and communicated orally) by mortal gurus, contrasted to Smriti, which was reminisced by common people. According to the Atharva Veda, the five sacred botanicals (healing balms) are asvattha, darbha, soma, cannabis, and rice. As per the Vedas, cannabis, one of five sacred plants, is considered a guardian angel that lived in its leaves. The Vedas refer to cannabis as a source of happiness, joy-giver, liberator that was benevolently consumed by the human being to attain a state of nirvana (delight and lose fear). Shiva (destroyer), the universally oldest known God, has millions of devotees. The devotees of Lord Shiva perform rituals and meditation by consuming milk and cannabis mixture (Bhang) prepared by a high priest. Sadhus (humans with spiritual oneness with Shiva) smoke 'Charas' and 'ganja' from chillums.

Cannabis-based formulations have been well known in the sub-continent for many centuries. They have been used during festivals and holy celebrations, the “Holi” (festival of colour) and “Shivratri” (night of Shiva). The major cannabis concoction consists of nuts (almonds, pistachios, poppy seeds), spices (pepper, ginger), and sugar are combined and boiled with milk or yogurt. Bhang is additionally rolled and eaten in small balls. The other cannabis-based preparations in India include ganja and charas. In general, people use cannabis-based products to feel rejuvenated and decrease fatigue during work or at the end of the day. Hindus consume cannabis-based products for spiritual rituals to seek out spirituality. Sadhus (Indian ascetics) have rejected worldly life and devoured cannabis-based products to attain spiritual liberation. By accentuating physical austerity through celibacy and fasting, cannabis helps sadhus transcend ordinary reality and achieve transcendence.

In the 18th century, during their initial trade with India, Britishers discovered chronic and widespread cannabis consumption and commissioned a large-scale study. This study resulted in the “Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report,” which mentioned the significant health concern regarding the abuse of cannabis. Therefore, the British empire appointed an Indian Government commission to regulate the cultivation, preparation, and trade of cannabis to enhance social wellbeing, essentially establishing a prohibition. The Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report of 1894, conducted over 100 years ago, is surprisingly relevant today. Cannabis continues to be available in India, and little has changed since the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report of 1894. Today, cannabis is readily available in India.

Interestingly, prohibition has been impossible due to the Hindu religious extremists and religious clerics who encourage dissent and make it difficult to enforce and possibly lead to the use of more dangerous narcotics. During the Hindu festival of Holi and Maha Shivratri, people consume bhang which contains cannabis flowers. According to one description, when the amrita (elixir of life) was produced from the churning of the ocean by the devas and the asuras as described in the Samudra Manthan, Shiva created cannabis from his own body to purify the elixir (angaja or “body-born”). Another account suggests that the cannabis plant sprang up when a drop of the elixir dropped on the ground. Thus, cannabis is used by sages due to its association with elixir and Shiva. Bhang is believed to cleanse sins, unite one with Shiva and avoid the miseries of hell in the future life. It is also believed to have medicinal benefits and is used in Ayurvedic medicine. In contrast, foolish drinking of bhang without rites is considered a sin.

IV Bahá'í and Cannabis

Bahá'í belief encourages and enthuses human beings to enhance an individual's survival and support the evolution and progression of society. Bahá'í discourses emphasize the oneness of God and religion, the unanimity of people and freedom from bias and partiality, the innate graciousness of the person, the advanced disclosure of spiritual reality. Furthermore, Bahá'í encourages the advancement of spiritual abilities, the amalgamation of devotion and service, the essential fairness of the genders, the congruence between religion and science, the importance of justice to all human actions, emphasizes education, and the crescendos of the relationships that are to bind together individuals, communities, and institutions as humanity advances towards its communal growth. The Kitáb-i-Aqdas is the holy book and is the book of laws. Bahá'u'lláh (The divine educator) restated the prohibition of the use of opium in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas. Later, Shoghi Effendi (the successor) asserted that one of the requirements for “a chaste and holy life” is “total abstinence” from opium, and similar habit-forming drugs (heroin, hashish, cannabis such derivatives, and hallucinogenic agents- lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), peyote and similar drugs). Bahá'í firmly believes that the user of these addictive substances, the buyer of these addictive substances, and the seller of these addictive substances are all deprived of the bounty and grace of God. However, recently, the use of some addictive substances (Marijuana) is not being prohibited for their consumption when prescribed as a therapeutic drug by a qualified physician [20]. Baháʼí authorities have spoken against intoxicant drugs since the earliest stages of the religion. In the Baha'i faith, alcohol and other drugs for intoxication are prohibited instead of appropriate medical use. However, Baháʼí practice is, such laws should be applied with “tact and wisdom.” Interestingly, tobacco use is an individual decision, and it is yet strongly frowned on but not explicitly forbidden.

V Buddhism and Cannabis

The five precepts of Buddhism that have persisted for thousands of years are as follows: Refrain from taking life, refrain from taking what is not given, refrain from the misuse of the senses, refrain from wrong speech, and refrain from intoxicants that cloud the mind. The Buddhists created these as a set of personal practices to protect an individual and the community. Recently, his Holiness, the Dalai Lama, has been involved in the benevolence of human healthcare. He has sincerely exhibited empathy, care, and kindness and has accentuated the importance of practicing personal and emotional hygiene in our daily lives. Dalai Lama does not support recreational consumption but currently favours medicinal Marijuana currently.

VI Confucianism and Cannabis

Confucianism was created by Chinese philosopher Confucius (~500 BC) and later established by Mencius. Intriguingly, there is evidence of cultivating hemp plants in the Confucian literature, but little is known about the use of cannabis among followers of Confucius.

VII Jainism and Cannabis

Jina Vardhamana Mahavira founded Jainism in India in the 6th century BC. It is a non-theistic religion formed due to the response in opposition to the doctrines of orthodox Brahmanism. Jainism preaches salvation by perfection through successive lives, non-injury to living organisms, and is well-known for its ascetics. Like Christianity, it does not explicitly reveal information regarding the use of cannabis. Nevertheless, based on the tenets and essence of Jainism, substances that are stimulating, intoxicating, or materials that poison the psyche (mind) and disrupt brain physiology (function) should be avoided. According to the Jains, Cannabis falls in the category above. However, recently due to the medicinal value of cannabis, the spiritual Jain leaders have not opposed the medicinal use of this ancient botanical to treat a few diseases.

VIII Judaism and Cannabis

It is a complex Jewish religious phenomenon that emphasizes the total way of life for the Jews. Judaism encompasses theology, law, numerous cultural rituals, and practices. Furthermore, the devotees follow a religious life following scriptures and rabbinic traditions. It is a monotheistic faith created by the ancient Hebrews. The belief in the religion is mainly illustrated by the faith in one transcendent God who revealed himself to Abraham, Moses, and the Hebrew prophets. Based on the historical literature and Hebrew Bible, cannabis may have been utilized ritually in early Judaism. Additionally, there is historical evidence of several cannabinoid compounds present in the ritual offerings in the Kingdom of Judah. However, some other spiritual leaders and historians do not agree with Judaism and Christianity [21].

Some scholars have theorized that cannabis may have been used ritually in early Judaism, though others have widely dismissed these claims as erroneous. Sula Benet in 1967 claimed that the plant kaneh bosm mentioned five times in the Hebrew Bible and used in the holy anointing oil of the Book of Exodus, was, in fact, cannabis, although lexicons of Hebrew and dictionaries of plants of the Bible identify the plant in question as either Acorus calamus or Cymbopogon citratus. In 2020 a study at Tel Arad, a 2700-year-old shrine then at the southern frontier of the Kingdom of Judah, found that burnt offerings on one altar contained multiple cannabinoid compounds, suggesting the ritual use of cannabis within ancient Judaism. In the modern era, Orthodox rabbi Moshe Feinstein stated that cannabis was not permitted under Jewish law due to its harmful effects. However, Orthodox rabbis Efrain Zalmanovich and Chaim Kanievsky stated that medical, but not recreational, cannabis is kosher. However, others have argued against this view and contended that cannabis could positively use religious experience within Judaism. Currently, several orthodox rabbis have not allowed the use of cannabis in Judaism. However, like the other religious leaders, orthodox rabbis are also considering the human use of cannabis for treating various pathological diseases.

IX Shinto and Cannabis

Shinto, “the way of kami” is commonly the sacred or divine power of various gods or deities. It is generally Japan's ethnic, spiritual values and traditions, and it differentiates the native Japanese beliefs from Buddhism. Interestingly, Shinto has no creator/initiator, holy scriptures, strict doctrines, but it has conserved its guiding principles throughout the centuries. Cannabis consistently has been part of Shintoism and has been admired for its purification capabilities by the priests. The Shinto priest shakes or waves Cannabis leaves to purge the sinful spirits and bless the followers. This customary practice is still being followed in the present day by the priest with cannabis wands (strips of the gold-coloured rind of cannabis stalks) and thick ceremonial ropes displayed at shrines woven from cannabis fibers.

X Sikhism and Cannabis

Sikhism was founded by Guru Nanak and consequently guided by a succession of nine other Gurus. Sikhism was established in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, and the followers are referred to as Sikhs. The followers refer to their faith as Gurmat (the Way of the Guru) and are colonized by a single spirit. Bhang, a beverage with leaves and flower buds of cannabis, has been used by Sikhs. Nihangs (the immortals) are armed Sikh soldiers who have used cannabis (bhang) before or after combat to provide a sympathetic urge (adrenaline rush, feeling of immortality/ invincibility) or to reduce pain. Therefore, the cannabis preparation is referred to as “Sukhni Dhaan” or “Sukkha Prasad” (Peace-Giver). However, drugs of abuse and alcohol are prohibited in Sikhism. In Sikhism, the First Sikh Guru, Guru Nanak, stated that using any mind-altering substance without medical purposes is a distraction to keeping the mind clean of the name of God. According to the Sikh Rehat Maryada, “A Sikh must not take hemp (cannabis), opium, liquor, tobacco, in short, any intoxicant. His only routine intake should be food and water”. However, there exists a tradition of Sikhs using edible cannabis, often in the form of the beverage bhang, particularly among the Sikh community of Nihang.

XI Taoism and Cannabis

Taoism believes in a positive mindset about life and considers tolerating and surrendering the blissful and carefree sides. It is a native religious and moral practice that has influenced Chinese living for centuries. Taoist shamans used cannabis for ritualistic purposes but were devoured only by the religious leaders.

XII Zoroastrianism and Cannabis

Zoroastrianism is an archaic pre-Islamic religion of Persia that still exists in the Indian sub-continent. Zoroastrianism inspired by Judaism and Christianity comprises both monotheistic and dualistic elements. The inheritors of Zoroastrian are known as Parsis, and they use cannabis in religious and mortuary practices. The evidence of the use of cannabis is found in Vendidad of the Zend-Avesta, Bangha (Bhang of Zoroaster), where cannabis is referred to as a “good narcotic.”

Major Use and Contraindications of Cannabis

Historically various ancient civilizations and religions have used Cannabis (Table 3) as an anaesthetic, anti-phlegmatic (anti-mucus), antiemetic, enemas (inserting solid/liquid into the rectum), and appetite stimulant. Additionally, this botanical was also to treat muscle spasticity, arthritis, asthma, bronchitis, cancer, convulsions, diarrhea/dysentery, earache, edema, glaucoma, gout, hemorrhage, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis), insomnia, joint pain, migraines, menstrual cramps, muscle spasms, infections (parasitic, bacterial), and sexual disorders (suppress sexual longing).

Table 3: Role of cannabis in various ancient civilizations.

|

Civilization |

Use

|

Purpose |

|||

|

Entheogen

(Spiritual/ Ritual

/ceremonial) |

Recreational

|

Medicinal |

Commercial/

Industrial |

||

|

Incan

|

Not

Clear |

||||

|

Aztec

|

Yes |

yes |

|

Pain

relief |

|

|

Roman

|

Yes |

yes |

yes |

Inducing

sleep, relieving pain, anti-microbial |

|

|

Ancient

Greek |

Yes |

yes |

yes |

Pain

relief, ti-inflammatory, wound healing, hemorrhage, anti-microbial (Cholera) |

|

|

Ancient

Egyptian |

yes |

Yes |

yes |

Anti-inflammatory,

pain relief, ophthalmic use (glaucoma), Feminine health (endometriosis,

menstruation) |

Fabrics,

ropes, |

|

Chinese

|

Yes |

Yes |

yes |

Pain

relief, |

Ropes,

Food, Fabric, Warfare, paper, Gout, Menstruation, gout, constipation,

rheumatism, |

|

Maya

|

Yes |

yes |

|

Pain

relief |

|

|

Indus

Valley |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Pain

relief |

|

|

Mesopotamian

|

Yes |

Yes |

yes |

Pain

relief |

|

Cannabis possesses a significant analgesic effect, and therefore it has been used to treat neuropathic pain associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis (MS), sickle cell disease, and migraine. Furthermore, Cannabis can significantly reduce chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cannabis is currently being investigated for its therapeutic potential to treat Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, post-traumatic stress disorder, Tourette syndrome, fibromyalgia, hypertension, chronic pain, migraine, and cachexia [22, 23]. Few research studies have shown the effectiveness of Cannabis in treating symptoms associated with Lou Gehrig's disease / amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (depression, appetite, spasms, drooling), dementia (reduce aggression and agitation), rheumatoid arthritis (decrease morning pain and improve sleep), Parkinson disease (improves pain, stiffness, and shakiness), and multiple sclerosis (improve symptoms such as muscle spasms and nerve pain).

While cannabis products may have therapeutic value in several disease states, cautions about their use have also emerged (Table 4). There are reports of Cannabis being contraindicated in stroke, depression, arrhythmia, and bipolar disorder. Furthermore, Cannabis should not be consumed during breastfeeding and pregnancy.

Figure 1: Different religions around the world are using cannabis products.

Table 4: Traditional, current, and possible future use of

Cannabis.

|

Organ System |

Traditional and Current use |

|

Brain |

Anaesthetic, epilepsy, seizure, convulsion,

multiple sclerosis, insomnia, migraine, Alzheimer’s disease, Lou Gehrig's

disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), Parkinson’s disease, post-traumatic

stress disorder, Tourette syndrome, cachexia, dementia (reduce aggression and

agitation), fibromyalgia, |

|

Ophthalmic |

Glaucoma |

|

Gastrointestinal |

Emesis, nausea, constipation (enemas), appetite

stimulant, inflammatory / irritable bowel disease (Crohn disease. ulcerative

colitis), diarrhea & dysentery, chemotherapy-induced nausea / vomiting, |

|

Respiratory / Pulmonary |

Asthma, bronchitis |

|

Cardiovascular |

Stroke, edema, hemorrhage |

|

Genitourinary tract |

Sexual disorders (suppress sexual longing), edema |

|

Muscle / Bones |

Arthritis, gout, muscle spasticity, |

|

Immune |

Infections (parasitic, bacterial), |

|

Endocrine |

Diabetes mellitus |

|

Cosmetics |

Hair, eye, facial, skincare products, anointing

oil |

|

Other |

Cancer, Pain (earache, menstrual cramp),

neuropathic pain associated with HIV and AIDS, rheumatoid arthritis, &

MS, Pain in patients sickle cell disease |

Conclusion

This chapter explored the “cannabis custom” in various civilizations and religions. The uninterrupted and continual human fascination with the recreational and beneficial effects has significantly enhanced the modern-day use of cannabis as a medicinal and commercial natural product. The medicinal, recreational, and commercial benefits of cannabis in a specific society have been constantly passed on to the subsequent generations, leading to the current traditional, spiritual, household, therapeutic, and commercial uses (Figure 1). Besides that, this section supports and lays the basis for validating the comprehensive, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic research required to comprehend better the prophylactic and therapeutic clinical relevance and applications of non-psychoactive cannabinoids in the therapeutic intervention of acute and chronic pathological conditions or disease states which will help to improve the legal status of this natural product.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely thank Harrison College of Pharmacy for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Article Info

Article Type

Review ArticlePublication history

Received: Wed 07, Sep 2022Accepted: Wed 21, Sep 2022

Published: Thu 13, Oct 2022

Copyright

© 2023 Muralikrishnan Dhanasekaran. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.JFNM.2022.01.02

Author Info

Rishi M. Nadar Kelli McDonald Jack Deruiter Suhrud Pathak Sindhu Ramesh Reeta Vijayarani Kruti Gopal Jayachandra Babu Ramapuram Kamal Dua Timothy Moore Jun Ren Muralikrishnan Dhanasekaran

Corresponding Author

Muralikrishnan DhanasekaranDepartment of Drug Discovery and Development, Harrison College of Pharmacy, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, USA

Figures & Tables

Table 1: Chronology and history of cannabis utilization.

|

Year |

Location |

Information on Cannabis Utilization |

|

4000 BC 2900 BC 2737 BC |

China

|

Pan-p’o village (Banpo) Fu His (Chinese emperor) Sheng-nung Pen-ts'ao Ching / Kang-mu, Materia

medica |

|

2000 BC |

India |

Ayurveda (Indian /Hindu Medical System) |

|

1550 BC 1450 BC 1213 BC |

Egypt |

Ebers Papyrus Exodus Ramesses II (Pharaoh) |

|

900 BC |

Northern Iraq, Southeastern Turkey |

Assyrians |

|

700 BC |

Persia |

Venidad (volume of the Zend-Avesta) |

|

450-200 BC |

Italy, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey |

Greco-Roman |

|

207 AD |

China |

Hua T’o (Surgeon) |

|

1025 |

Persia |

Avicenna (Medical writer) |

|

1300 |

India to Eastern Africa |

Arab traders |

|

1500 |

Spain to Americas |

Spanish Conquest |

|

1798 |

France |

Napoleon Bonaparte |

|

1839 |

Britain |

William O’Shaughnessy (Medicinal Property) |

|

1900 |

|

Medical Cannabis (OTC product) |

|

1914 |

United States of America |

Harrison Act (Cannabis prescription) |

|

1937 |

United States of America |

Marihuana Tax Act |

|

1964 |

Israel |

Discovery of THC (Raphael Mechoulal) |

|

1970 |

United States of America |

Classified as Schedule 1 Drug |

|

1988 |

United States of America |

Discovery of cannabinoid Receptors (Allyn

Howlett) |

|

1900– Till date |

Around the World |

Legalization of Cannabis |

OTC:

Over The Counter product of cannabis.

Table 2: Important features of religious beliefs Cannabis and

use.

|

Major Religion |

Spiritual |

Recreational |

Medicinal |

Commercial |

|

Christianity |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

|

Islam |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Hinduism |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Bahá'í |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Buddhism |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Confucianism |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

|

Jainism |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Judaism |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

|

Shinto |

Yes |

|

|

|

|

Sikhism |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Taoism |

Yes |

No |

Not Clear |

No |

|

Zoroastrianism |

Yes |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Not Clear |

Table 3: Role of cannabis in various ancient civilizations.

|

Civilization |

Use

|

Purpose |

|||

|

Entheogen

(Spiritual/ Ritual

/ceremonial) |

Recreational

|

Medicinal |

Commercial/

Industrial |

||

|

Incan

|

Not

Clear |

||||

|

Aztec

|

Yes |

yes |

|

Pain

relief |

|

|

Roman

|

Yes |

yes |

yes |

Inducing

sleep, relieving pain, anti-microbial |

|

|

Ancient

Greek |

Yes |

yes |

yes |

Pain

relief, ti-inflammatory, wound healing, hemorrhage, anti-microbial (Cholera) |

|

|

Ancient

Egyptian |

yes |

Yes |

yes |

Anti-inflammatory,

pain relief, ophthalmic use (glaucoma), Feminine health (endometriosis,

menstruation) |

Fabrics,

ropes, |

|

Chinese

|

Yes |

Yes |

yes |

Pain

relief, |

Ropes,

Food, Fabric, Warfare, paper, Gout, Menstruation, gout, constipation,

rheumatism, |

|

Maya

|

Yes |

yes |

|

Pain

relief |

|

|

Indus

Valley |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Pain

relief |

|

|

Mesopotamian

|

Yes |

Yes |

yes |

Pain

relief |

|

Table 4: Traditional, current, and possible future use of

Cannabis.

|

Organ System |

Traditional and Current use |

|

Brain |

Anaesthetic, epilepsy, seizure, convulsion,

multiple sclerosis, insomnia, migraine, Alzheimer’s disease, Lou Gehrig's

disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), Parkinson’s disease, post-traumatic

stress disorder, Tourette syndrome, cachexia, dementia (reduce aggression and

agitation), fibromyalgia, |

|

Ophthalmic |

Glaucoma |

|

Gastrointestinal |

Emesis, nausea, constipation (enemas), appetite

stimulant, inflammatory / irritable bowel disease (Crohn disease. ulcerative

colitis), diarrhea & dysentery, chemotherapy-induced nausea / vomiting, |

|

Respiratory / Pulmonary |

Asthma, bronchitis |

|

Cardiovascular |

Stroke, edema, hemorrhage |

|

Genitourinary tract |

Sexual disorders (suppress sexual longing), edema |

|

Muscle / Bones |

Arthritis, gout, muscle spasticity, |

|

Immune |

Infections (parasitic, bacterial), |

|

Endocrine |

Diabetes mellitus |

|

Cosmetics |

Hair, eye, facial, skincare products, anointing

oil |

|

Other |

Cancer, Pain (earache, menstrual cramp),

neuropathic pain associated with HIV and AIDS, rheumatoid arthritis, &

MS, Pain in patients sickle cell disease |

References

1. Hou JP (1977) The

Development of Chinese Herbal Medicine and the Pen-ts'ao. Comp Med East West

5: 117-122. [Crossref]

2. Aldrich M (1997)

History of Therapeutic Cannabis. In: Mathre ML (ed) Cannabis in Medical

Practice: a Legal, Historical and Pharmacological Overview of the Therapeutic

use of Marijuana. McFarland & Co., pp 35-55.

3. Antonio Waldo Z

(2006) History of cannabis as a medicine: a review. Braz J Psychiatry

28: 153-157. [Crossref]

4. Bonini SA, Premoli

M, Tambaro S, Kumar A, Maccarinelli G et al. (2018) Cannabis sativa: A

comprehensive ethnopharmacological review of a medicinal plant with a long

history. J Ethnopharmacol 227: 300-315. [Crossref]

5. Petrovska BB (2012)

Historical review of medicinal plants' usage. Pharmacogn Rev 6: 1-5. [Crossref]

6. Rabiee R, Lundin A,

Agardh E, Forsell Y, Allebeck P et al. (2020) Cannabis use, subsequent other

illicit drug use and drug use disorders: A 16-year follow-up study among

Swedish adults. Addict Behav 106: 106390. [Crossref]

7. Ghiabi M,

Maarefvand M, Bahari H, Alavi Z (2018) Islam and cannabis: Legalisation and

religious debate in Iran. Int J Drug Policy 56: 121-127. [Crossref]

8. Gnoli G SSA (1988)

‘Bang’, encyclopedia iranica, vol III.

9. Allegretti JR,

Courtwright A, Lucci M, Korzenik JR, Levine J (2013) Marijuana use patterns

among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19:

2809-2814. [Crossref]

10. Campos AC, Araújo

Moreira F, Gomes FV, Aparecida Del Bel E, Silveira Guimarães F (2012) Multiple

mechanisms involved in the large-spectrum therapeutic potential of cannabidiol

in psychiatric disorders. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 367:

3364-3378. [Crossref]

11. Carrier N,

Klantschnig G (2012) Africa and the War on Drugs. Zed Books, London.

12. Mills PM, Penfold N

(2003) Cannabis abuse and anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 58: 1125. [Crossref]

13. Robins P (2016)

Middle east drugs bazaar production, prevention and consumption. Oxford

University Press, USA.

14. Safian DYHM (2013)

An analysis on Islamic rules on drugs. Int J Education Res 1: 1-16.

15. Afsahi K, Darwich S

(2016) Hashish in Morocco and Lebanon: A comparative study. Int J Drug

Policy 31: 190-198. [Crossref]

16. Nahas GG (1982)

Hashish in Islam 9th to 18th century. Bull N Y Acad Med 58: 814-831. [Crossref]

17. Kamarulzaman A,

Saifuddeen SM (2010) Islam and harm reduction. Int J Drug Policy 21:

115-118. [Crossref]

18. Johnson BA (2011)

Addiction Medicine. Science and Practice. Springer.

19. Ferrara MS (2016)

Sacred bliss: a spiritual history of cannabis. Lanham : Rowman &

Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

20. Bahji A (2019) What

are the key considerations for clinicians treating Bahá'í patients with

psychiatric disorders? The Lancet Psychiatry 6: 641. [Crossref]

21. Zdrojewicz Z, Pypno

D, Cabała K, Bugaj B, Waracki M (2014) Potential applications of marijuana and

cannabinoids in medicine. Pol Merkur Lekarski 37: 248-252. [Crossref]

22. Schwantes An TH, Zhang J, Chen LS, Hartz SM, Culverhouse RC et al. (2016) Association of the OPRM1 Variant rs1799971 (A118G) with Non-Specific Liability to Substance Dependence in a Collaborative de novo Meta-Analysis of European-Ancestry Cohorts. Behav Genet 46: 151-169. [Crossref]

23. Tramer MR, Carroll D, Campbell FA, Reynolds DJM, Moore RA et al. (2001) Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. BMJ 323: 16-21. [Crossref]