Advanced Trainee-Led Physician Clinical Examination Workshop: Improving Training and Culture

A B S T R A C T

Background: Near-to-peer teaching involves more experienced learners acting as tutors for junior colleagues and has significant theoretical benefits for both teachers and learners [1-3].

Aim: Development, implementation, and assessment of a weekend examination preparation workshop by Royal Australasian College of Physicians Advanced Trainees (ATs) for Basic Physician Trainees (BPTs), using a near-to-peer framework.

Methods: A two-day offsite course was designed by ATs. Day 1 - subspecialty short-case demonstrations, followed by small-group examination practice. Shared downtime was organized for the evening. Day 2 - two exemplar long-case presentations by ATs with consultant examiner feedback, followed by interactive small-group sessions focusing on presenting long-cases.

Results: A post-course survey was completed by 72% of BPTs (13/18) and 88% of ATs (8/9). Responses demonstrated that all BPTs would recommend this workshop to peers. 84% (11/13) found the course material very useful. 62% (5/8) ATs felt their leadership and teaching skills had significantly improved. BPTs reported that the AT long-case demonstrations were highly useful. Negative feedback included the venue, course timing, and lack of patients with clinical signs.

Conclusion: This innovative AT-led examination preparation workshop significantly enhanced training culture and candidate well-being. ATs benefited with increased confidence in their ability to lead and teach.

Keywords

Clinical exam, workshop, near to peer teaching, near to peer learning, short case, long case, training culture

Background

Near-to-peer teaching involves more experienced learners acting as tutors for junior colleagues [1]. This concept has been extensively studied amongst medical schools in the setting of junior doctors teaching medical students [1]. Studies suggest that peer teachers are more relatable to medical students than senior clinicians and other faculty members [1, 2]. This relationship often allows open discussion of challenges faced during training [1, 2]. The concept of cognitive congruence where the teacher and learner have a similar knowledge base and are therefore closer in skill set has shown to be beneficial for adult learners [1]. Near-to-peer learning also fosters a positive and safe educational environment and results in reduced stress and greater achievement by students [3]. Near-to-peer teaching also alleviates the burden on institutions to routinely provide teachers at a senior (consultant) level [4]. This is a concept that can be extended to the teaching resources available for physician trainees. The benefits of near-to-peer learning also extend to the teacher. Delivery of peer-learning equips the teacher for their role as an educator as a future physician [4]. It allows training doctors to develop leadership skills, extended their ability to give constructive feedback and promote education as a part of their role as physicians [2]. These benefits seen with near-to-peer teaching amongst medical students may also extend to Basic Physician Trainees (BPTs) and Advanced Trainees (ATs) as part of exam preparation and improvement in clinical skills set.

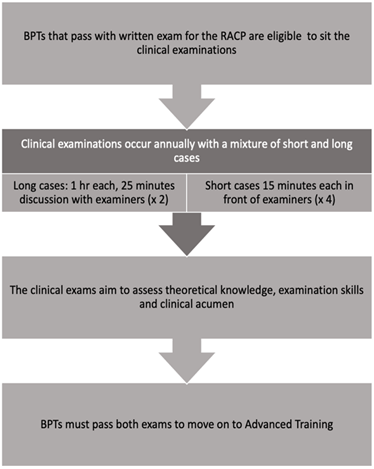

The Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) mandates physician training to comprise 36 months of Basic Physician Training with placements in generalist and specialist medical rotations in both tertiary and regional centers. Graduation to advanced training is performed after completion of a written examination and clinical examination in the final BPT year [5]. Clinical examinations occur once yearly with a mixture of short and long cases after the written examinations (Figure 1). The purpose of the written exams is to allow trainees to develop a theoretical knowledge base in internal medicine. The clinical exams are designed to assess trainee knowledge, examination technique, communication, diagnostic and clinical management skills. The short case exams last for 15 minutes in front of an examiner, where trainees are instructed to examine a major physiological system of the body and proceed to systematic assessment for relevant pathological stigmata.

Figure 1: Adapted from Royal college of physicians, the flow diagram of exam structure [5].

The aim of these cases is to assess trainees on their ability to examine accurately, efficiently, synthesise clinical signs and discuss to formulate a diagnosis with the examiner. Long cases are designed to assess the trainee’s ability to take a medical and social history, do a comprehensive physical examination, and identify a patient’s management priorities pertaining to treatment and prognosis. Trainees are allocated one hour with the patient and 25 minutes of discussion time with the examiners. Examiners assess a trainee’s ability to accurately identify patient care issues and develop diagnostic and treatment plans for each issue. The clinical exam consists of two long and four short cases. BPTs have approximately four months in which to prepare for these examinations after they have passed the written examination [5].

Success in both written and clinical exams is required for trainees to progress to highly competitive AT placements. These high-pressure exams and narrow timeframes coupled with workplace pressures have an impact on trainee mental health. The exams are also high stakes, as there is only one sitting each year. Failed candidates cannot progress to advanced training and must repeat the entire year of training. The financial costs of the exam are also high ($8353 AUD, not including travel, accommodation, and lost earning potential due to study leave) [6]. Recently, junior doctor mental health and suicide rates have received media attention [6]. In a psychological survey of Australian doctors, 25% of trainees had previous thoughts of suicide [7]. The competing pressures of exam stress, unsupportive workplace cultures, and demanding service requirements contribute to these poor mental health outcomes for trainees around Australia [5, 7, 8].

There are also several factors that engender negative social interdependence [9]. BPTs may hide cases from each other because of the scarcity of patients in the hospital who can be used for long case practice. Perceptions that a limited number of candidates can be afforded a pass in order to restrict entry to the limited number of advanced trainee positions available. BPTs can therefore become obstructive or unhelpful towards their colleagues in the hope of gaining an advantage for the clinical examination. Overall, this leads to significant anxiety amongst BPTs. They are usually employed in an inherently stressful role as a medical registrar. They often have young families at home. They are financially stretched by the cost of the clinical examination. Therefore, they are partially reliant on the educational support programme provided by the hospital for both their success in the examination and their overall well-being. The use of interactive and innovative teaching methods may not only introduce adult learning concepts into exam preparation but may ameliorate some of the anxiety related to clinical exam preparation.

In the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), the ACT Network Physician Training Committee (PTC) oversees the basic physician training programme and examination preparation for its trainees. To improve training ethos, fostering a more collegial culture of training amongst the BPTs and ATs was seen to be a worthwhile goal. We organized a weekend workshop in conjunction with the PTC led by the ATs to prepare BPTs for their clinical exam and improve trainee well-being. Furthermore, formal leadership training for ATs is often limited, and leadership is a core skill for ATs to develop as they are in transition to becoming consultants. It was hypothesised that this workshop might help augment AT leadership and teaching skills. The aims of the workshop were to:

i. Improve teaching culture and perceived collegiality,

ii. Increase AT involvement in the teaching programme and foster/develop leadership skills,

iii. Assess BPT and AT experience of workshop based on the utility of course materials and their willingness to recommend to peers,

iv. Improve BPT examination skills and confidence.

Unlike other centers within Australia where workshops such as these are primarily driven by consultant physicians, this programme was designed by trainees, for trainees, with consultant physician consultation. The structure of the workshop was designed with adult learning concepts in mind to allow for observation and experimentation by trainees for their clinical exam techniques with an opportunity to receive feedback and reflect upon their performance.

Summary of the Workshop and Resources

A two-day workshop consisting of short and long case topics was formulated. The course was convened at a location external to the hospital with overnight accommodation to create an immersive and relaxing environment. BPTs were given course materials to annotate and take home. These booklets consisted of previous exam material complied by ATs in their subspecialty areas. Additional resources including four volunteers, eight ATs, two consultant examiners for the live long cases.

I Workshop Outline

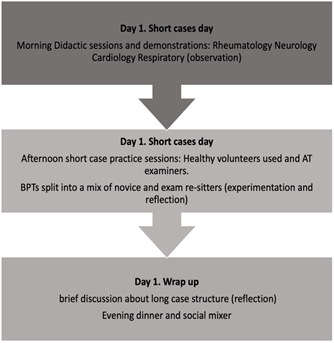

The two-day workshop consisted of short case examination sessions on day 1 (Figure 2A) and long case teaching points and demonstrations on day 2 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2A: Day 1 short cases day.

Figure 2B: Day 2 long cases day.

i. Day 1

The initial day consisted of various subspecialty short case demonstrations and presentations (observation), followed by small group examination practice with the BPTs. Small groups were structured so that exam re-sitters were paired with novices and an AT supervised each group. This allowed BPTs to refine their clinical examination skills (experimentation) using healthy volunteers and receive feedback (Figure 2A). The daytime academic activity was followed by an evening workshop dinner and social event. This was to allow for trainee reflection, debriefing, and social interaction.

ii. Day 2

Two demonstration long cases were presented by AT volunteers in a realistic examination format to college examiners to demonstrate different presentation styles under exam conditions. Here the AT presenters received constructive feedback in front of the BPTs audience from the college examiners, with a discussion of and reference to the RACP exam marking criteria (Figure 2B).

Exam candidates were then split into small groups to improve discussion techniques for long case presentations with feedback from ATs. In the afternoon session, BPTs were given a series of pre-written long cases to critically review in small groups, tutored by ATs. BPTs then presented a consensus on the main issues of the cases, actively restructured pre-written cases, and received constructive feedback (Figure 2B). The workshop concluded with presentations on psychosocial self-care techniques, a discussion on presentation styles, and an opportunity for questions from the BPTs. A survey was distributed to all attendees after the workshop but prior to the exam. Questions asked responders to rate their experiences as excellent, very good, good, fair or poor. Trainees were encouraged to provide feedback regarding the timing of the workshop. Participants were given the opportunity to provide free-text qualitative responses. A second survey was also sent to the ATs, only asking them about their experience and motivation to participate in the organizing and teaching as part of the workshop.

Results

I Baseline Data

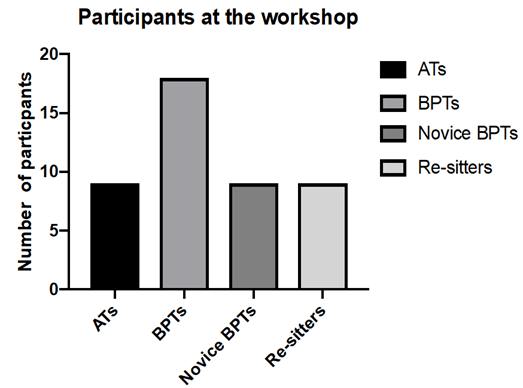

A total of 18 of 19 sitting exam candidates attended the workshop with nine ATs and two consultants. The workshops were led by the ATs. Of the BPTs attending, 9 were re-sitting the exam one or more times (50%), whilst the remaining 9 (50%) were attempting the exam for the first time (Figure 3). Survey of BPTs revealed 13 (72%) BPTs completed the post-workshop survey, while 8 (88%) ATs completed the second survey designed for ATs only.

Figure 3: AT and BPT participant break down.

II Overall Course Feedback

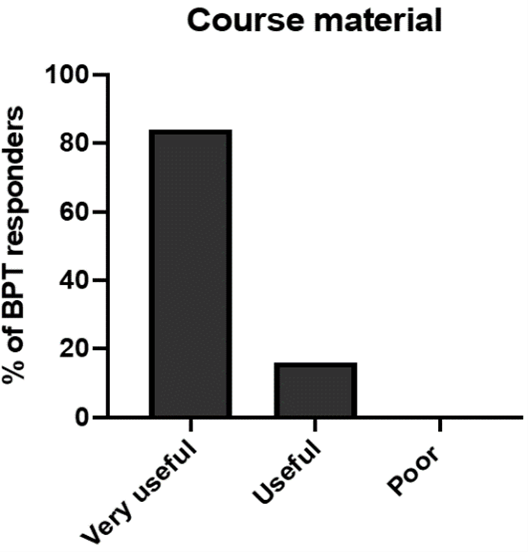

Course materials were considered very useful by 84% of trainees, with some reporting they should have been distributed prior to the course (Figure 4). All trainees were asked if they would recommend the course again, 70% of responders responded with “highly likely”, while the remaining 30% reported “likely to recommend”.

Figure 4: Participant opinion regarding course materials.

III Specific Feedback

BPTs provided written comments about the workshop. The most favoured sessions were the short and long case demonstrations. BPTs would have preferred patients with clinical signs and symptoms over healthy volunteers to practice examinations on and would have liked the opportunity to perform their own long cases for feedback. Live long case composition and demonstration sessions were regarded as highly valuable experiences. Overall, the trainees re-sitting the exam reported feeling more supported during the 2019 exam preparation than in prior years; open text responses indicated greater AT support both at the workshop and thereafter. Trainees indicated they would have liked an allocated AT mentor for the year’s exam preparation. The BPTs reported considerable stress during their exam preparation period, with competing priorities of clinical workload and after-hours rosters impacting their ability to practice for the exam and maintain work-life integration.

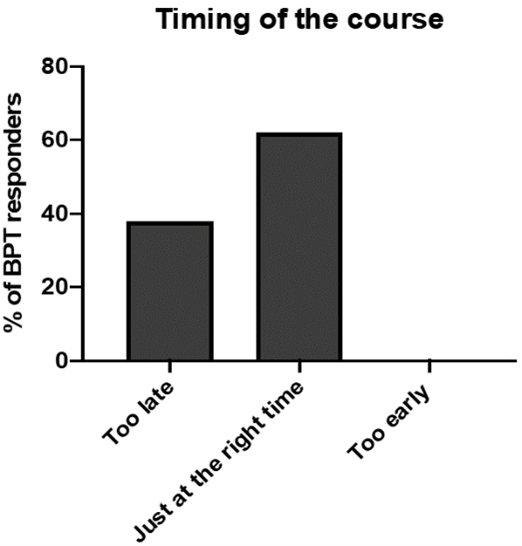

IV Timing

The 2-day duration of the course was considered optimal duration by 61% of trainees and was held at an appropriate time within the clinical year. However, 38% felt it was held too close to the exam (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Participant opinion regarding course date/timing.

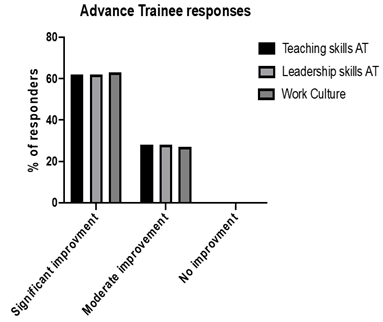

V Advance Trainee Feedback

ATs provided feedback about their impetus to participate which included: to pass on their skills, invest in the teaching programme, aid BPTs and improve training culture. At the completion of the course, 62% of ATs reported an improvement in self-perceived leadership and teaching skills. When asked about the positive impact on training culture, 62% reported there was an improvement, with all ATs likely to participate again in the workshop if it is run the following year (Figure 6). Barriers to AT participation included workload, weekend shifts, a lack of confidence regarding their own teaching skills and travel costs involved.

Figure 6: Advance trainees’ perspective on the course’s impact on leadership skills, teaching skills and work culture.

VI Venue and Conference Facilities

The accommodation was rated “excellent” by 62% of responders, whilst another 23% rated it as “very good”, 51% of responders felt the venue was “very good” as a teaching location. Open text feedback reflected lack of dedicated conference facilities, ambient noise and issues with information technology resources available at the venue being a limitation.

Discussion

This Physician clinical exam preparation workshop is an innovative AT-driven teaching initiative in Australia. The key facilitators of this programme’s success included the PTC, ATs and administrative staff, who contributed their personal time to assist in this workshop. The findings of our report suggest that this teaching model is effective in improving work culture, clinical examination and presentation skills among BPTs. The programme simultaneously benefits participating ATs, who reported greater confidence in their teaching and leadership skills. Near-to-peer teaching in the setting of Basic Physician Trainees appears to be cost-effective, feasible and improves skill acquisition and confidence among all participants. The structure and concept of this workshop were based on Gagne’s instructional model, incorporating adult learning principles (see Appendix 1) [10-12]. The integrative and interactive nature of this workshop rests on a social-cognitive model of education, by which a community approach to learning encourages BPTs to be active participants in their own learning and teaching. It allows colleagues to be involved as teachers and learners and shapes the trainee’s experiences [13, 14]. Social cognitive teaching also draws on the impact of the environment on learning. Fostering an immersive setting in which ATs could teach BPTs, the workshop created both an informal and undisturbed environment for BPTs skills acquisition and consolidation. Subsequently, post-workshop, ATs were more involved in teaching and BPTs felt more comfortable approaching ATs for assistance with exam preparation.

The course was considered highly valuable to BPTs, especially long case demonstrations and observed practice of short cases. This form of multisource feedback in medical education allows for peer-to-peer feedback, which is often considered a more valid form of assessment of the learners’ abilities, as compared to formal assessments alone [2, 3]. AT long case demonstrations with live examiner feedback allowed trainees to observe and subsequently experiment with a variety of different presentation styles. Didactic sessions involving theory and practice points were considered helpful in terms of content. However, BPT feedback suggested interactive sessions with demonstrations were of most use. BPT responses regarding the use of healthy volunteers did raise concerns that trainees had not seen enough patients during their own self-directed study. It remains unclear the degree of active versus passive learning undertaken by BPTs in their own time.

The key aim of the workshop was to improve training culture and help manage exam stress. The social function held during the workshop was an opportunity for trainees to integrate. Both ATs and BPTs reported the social event lead to a more collegial environment during the workshop and had a positive flow-on-effect in the workplace subsequent to the weekend. Improving educational culture in many institutions is frequently overlooked but can have a considerable impact on trainee motivation, retention and success rates [15]. Furthermore, peer teaching often provides trainees the opportunity to become crucial role models and mentors to junior doctors, which is a skill they may continue to foster during their careers [16]. By integrating trainees as a part of this workshop, the relationship between ATs and BPTs appeared to develop and improve the overall teaching culture. BPTs reported that AT support was valuable during exam preparation and qualitative feedback included the request for AT mentors in the following academic year. The workshop also assisted ATs development of leadership and teaching skills and promoted an environment in which trainees could extend their teaching style. Trainees that are involved in convening peer teaching in large group settings may enhance their leadership skills [1, 2]. Furthermore, trainees involved in peer teaching are more likely to continue to engage in teaching roles once they are qualified physicians [4]. As noted by our survey results, all ATs indicated that they felt their leadership and teaching skills had improved due to participation and expressed enthusiasm for involvement in future workshops.

A limitation of this workshop was the time of the clinical year in which it was held. BPT feedback indicated the workshop would have offered greater benefit earlier in the course of their exam preparation when clinical examination of healthy volunteers would hold more relevance. It is possible that a course date earlier in the academic year would have built the foundations for a more interactive and collegial approach to exam preparation among the BPT cohort and fostered relationships with the AT workforce. BPTs also reported that having access to course material earlier in their clinical examination preparation would have been useful. The venue was considered suboptimal as a teaching location due to disruption, ambient noise and limited conference facilities. Assessment of workshop experience was limited by lack of specific feedback given by trainees.

Future directions to improve the workshop would include a review of the timing of the course, teaching venue, structure of interactive sessions and early distribution of course materials for trainees. Trainee feedback indicated a strong preference for authentic patients with demonstrable pathology in place of health volunteers. A session on “key clinical signs” at the commencement of exam preparation would likely aid trainees in eliciting pathological signs. Reflecting on long case teaching, trainees may benefit from presenting cases in which they had previously encountered difficulties within a group setting, in addition to the novel long case demonstrations. Future assessment of the course by trainees may require either face-to-face feedback at the end of the course, or a survey done on-site during the workshop to improve response rate and give more insight into course strengths and potential improvements. Consideration of an AT mentorship programme at the start of basic training may facilitate working relationships between BPTs and ATs at the start of training and foster a supportive training environment. The 2020 workshop was subsequently canceled due to the COVID-19 SARS-CoV-2 pandemic; however it has been organized again for 2021.

Conclusion

This AT-lead clinical exam workshop for BPTs is an innovative addition to the models for physician exam preparation. This workshop, held by trainees for trainees, was a proof-of-concept programme, evaluating near-to-peer teaching to improve training culture, the basic physicians’ training programme, and exam success rates. Some logistical concerns remain to be addressed in future workshops. However, the initial aims of this pilot programme were met, and trainees appeared to benefit on multiple levels including fostering a more collegiate working environment between BPTs and ATs. The strength of this programme lies in the substantially improved AT leadership skills and BPT well-being.

Practice Points

i. Near-to-peer teaching is an effective teaching method to enhance preparation for the clinical examination.

ii. The Trainee-led workshop significantly improved training culture and well-being for all participants.

iii. Encouraging Advanced Trainees to utilize adult learning principles to teach junior trainees enhanced Advanced Trainee leadership and teaching skills.

iv. Undertaking a workshop external to the hospital academic setting facilitated a productive learning environment and improved collegiality in a social setting.

v. The use of live demonstrations, clinical skills and course material compiled by Advance Trainees for BPTs was considered highly valuable for exam preparation.

Author Contributions

Dr. Prianka Puri is a Nephrologist at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s hospital and completed her Advanced training at the Canberra Hospital. She has an interest in medical education and holds a Master of Public Health. She was the co-founder of this workshop and implemented it in practice in 2019 at The Canberra Hospital; Dr. Alice Kennard is a Nephrologist at The Canberra hospital with an interest in medical education and research. Dr. Kennard has obtained her master’s in public health and has undertaken her PhD. She is the founder and director of the renal supportive care service in The Australian Capital territory and coordinates the Nephrology department’s training programme; Dr. Luke Williamson is a Rheumatology Advanced trainee who has passed both the MRCP and FRACP examinations. He has an interest in medical education and is currently undertaking his master’s in medical education with the University of Dundee; Dr. Ashwin Swaminathan an Infectious Diseases specialist, and both the director of the General medicine and Physicians training programme in the Australian Capital Territory. Dr. Swaminathan has led the physicians training programme for the last 3 years and was instrumental in facilitating this Workshop.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Consent

The participants consent to publish survey data was obtained at the time of the survey completion. All participant data was anonymous as survey results were anonymous.

Acknowledgment

Authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of The Canberra Hospital Physicians Training Committee, administrative staff, healthy volunteers, and the Advanced Trainees involved in the Workshop.

Abbreviations

BPT: Basic Physician Trainee

AT: Advanced Trainee

RACP: Royal Australasian College of Physicians

FRACP: Fellowship of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Appendix

Adapted from Gagne’s instructional model [10, 11]:

i. Gaining attention

ii. Informing learner of objectives

iii. Stimulating recall of prior learning

iv. Presenting the stimulus material

v. Providing learning guidance

vi. Eliciting the performance

vii. Providing feedback about the correctness of the performance

viii. Assessing the performance

ix. Enhancing retention and transfer.

Article Info

Article Type

Research ArticlePublication history

Received: Sat 13, Mar 2021Accepted: Wed 07, Apr 2021

Published: Tue 08, Jun 2021

Copyright

© 2023 Prianka Puri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.JCMCR.2021.01.01

Author Info

Prianka Puri Alice Kennard Luke Williamson Ashwin Swaminathan

Corresponding Author

Prianka PuriDepartment of Renal Medicine, The Canberra Hospital, Canberra, ACT, Australia

Figures & Tables

References

1. Frey JH, Whitman NA

(1990) Peer Teaching: To Teach Is to Learn Twice. Teach Sociol 18: 265.

2. Ten Cate O, Durning

S (2007) Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory

to practice. Med Teach 29: 591-599. [Crossref]

3. Arnold L, Shue CK,

Kritt B, Ginsburg S, Stern DT (2005) Medical students’ views on peer assessment

of professionalism. J Gen Intern Med 20: 819-824. [Crossref]

4. Abela J (2009)

Adult learning theories and medical education: a review. 21: 7.

5. RACP program. Basic

Training Curriculum. The

Royal Australasian College of Physicians.

6. RACP Basic training

fees. The Royal Australasian College of Physicians.

7. National Mental

Health Survey of Doctors and Medical Students (2019).

8. Worthington E

(2017) Doctor suicides prompt calls for overhaul of mandatory reporting laws.

9. Johnson DW, Johnson

RT, Smith K (2007) The State of Cooperative Learning in Postsecondary and

Professional Settings. Educ Psychol Rev 19: 15-29.

10. Buscombe C (2013)

Using Gagne’s theory to teach procedural skills. Clin Teach 10: 302-307.

[Crossref]

11. Gagné RM (1977) The

conditions of learning. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

12. Taylor DCM, Hamdy H

(2013) Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in

medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach 35: e1561-1572. [Crossref]

13. Harden RM (2006)

Trends and the future of postgraduate medical education. Emerg Med J 23:

798-802. [Crossref]

14. Mann KV (2011)

Theoretical perspectives in medical education: past experience and future

possibilities: Pedagogy: past and future. Med Educ 45: 60-68. [Crossref]

15. Yardley S,

Teunissen PW, Dornan T (2012) Experiential learning: AMEE Guide No. 63. Med

Teach 34: e102-e115. [Crossref]

16. Kiewkor S,

Wongwanich S, Piromsombat C (2014) Empowerment of Teachers through Critical

Friend Learning to Encourage Teaching Concepts. Proc Soc Behav Sci 116:

4626-4631.