Journals

Depression and Anxiety identified to be the Most Commonly Reported Mental Health problems by General Practitioners

A B S T R A C T

Introduction: General practitioners (GPs) regularly provide care for adult patients with psychological/psychiatric problems and prescribe appropriate medications (either independently or in consultation with a psychiatrist).

Objectives: We established a list of the most common mental health problems GPs encounter during daily practice and suggested solutions to increase their competence in identifying and selecting appropriate treatments.

Methods: We designed and conducted a voluntary survey; we collected data from 55 outpatient GPs at multiple outpatient clinics in Novi Sad, Serbia, which has a Universal Health Care System. Collected data were analyzed using including descriptive and analytical statistics.

Results: Psychological/psychiatric problems were most commonly identified during GPs’ interviews with patients (70.9%) and by utilizing evidence-based behavioral health-screening instruments. Anxiety (80.0%) and depression/depressed mood (78.2%) were the two most frequently reported problems. To increase competence in diagnosing and treating patients with psychological/psychiatric problems, 76.3% of GPs identified the need for additional educational opportunities that address psychotropic medications used for depression, and 54.5% identified the need for topics related to initiating and managing antidepressant therapy.

Conclusions: The most common psychological/psychiatric problems that GPs encounter in their practice are anxiety and depression. To increase competency in treating these problems, GPs will benefit from additional learning opportunities and training related to assessment and pharmacological treatment of patients with depression and anxiety disorders.

K E Y W O R D S

General practitioner, psychological problems, psychiatric problems, depression, anxiety, antidepressant drugs, education

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Depression and Anxiety identified to be the Most Commonly Reported Mental Health problems by General Practitioners According to the World Health Organization, mental health problems present with a range of symptoms and negatively affect many areas of life [1]. Mental health disorders can present as changes in thoughts, emotions, and behavior, and they can affect familial relationships and social interactions. Furthermore, a large percentage of the World population with mental health disorders does not have timely access to psychiatric care [2-4].

Anxiety and depression are among the most common mental health disorders that general practitioners (GPs) encounter in their daily practice. They are often comorbid with other mental health disorders [5].

Both depression and anxiety disorders can present at different developmental stages, in children, adolescents, and the adult population, and symptoms can present in both males and females regardless of geographical location [6]. Depression, if severe, can be debilitating and affect all areas of a person’s life, including family and work, and be accompanied by a loss of energy; sleep disturbances; memory problems; somatic symptoms; and feeling sad, hopeless, helpless, guilty, and suicidal, which, in some cases, requires urgent assessment and hospitalization [7]. Clearly, diagnosing mental disorders early and effectively referring the individual to a psychiatrist for treatment is of vast importance [7].

Further, there is a reported increase in mortality and decrease in life expectancy in people with mental illness [8, 9]. Suicide as well as declining physical health are major concerns in patients with mental illness. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among 15–29-year-olds [10]. In addition, 78% of global suicides occur in low- and middle-income countries [10]. Patients with mental illnesses have more co-occurring chronic illnesses compared to the general population including high blood pressure, obesity, heart disease, and diabetes [11, 12]. In addition, there are multiple causes for decrease in life expectancy in mentally ill patients, including poor compliance with treatment, not seeing a GP on a regular basis, medication side effects, increased smoking, and lifestyle issues. These findings highlight the importance of GPs working closely with psychiatric patients and coordination between psychiatrists and other subspecialties, focusing on prevention, lifestyle changes, and monitoring patients’ compliance.

The role of GPs will only become more vital as the shortage of mental health workers expands and wait time for appointments increases [4]. Therefore, we sought to identify how GPs assess, diagnose, treat, and refer patients with mental health disorders as well as to identify the most common mental disorders they encounter and their comfort level treating those disorders. The study was conducted in Novi Sad, Serbia within the Universal Health Care System.

Methods

This study was approved in October 2017 by an ethics committee of the Community Health center in Novi Sad, Serbia and conducted at multiple outpatient GP clinics. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

The study on which one was based was conducted at the Department of Psychiatry, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA and participants were family practice providers and pediatricians [13].

Our thirteen-item questionnaire was adjusted to the Universal Health System in Novi Sad; Serbia and a replication study was conducted. We designed and conducted a survey and collected data from 55 GPs working at outpatient clinics in Novi Sad, Serbia. Participants were recruited from November 1 to December 31, 2017. Collected data were statistically analyzed using descriptive and analytical statistics.

Figures

Figure 1: The most common psychological problem encountered in general practitioners’ practice

Figure 2: Reported symptoms of anxiety by age of the patients

Figure 3: The most common way psychological/psychiatric problems are identified during a general practitioner visit

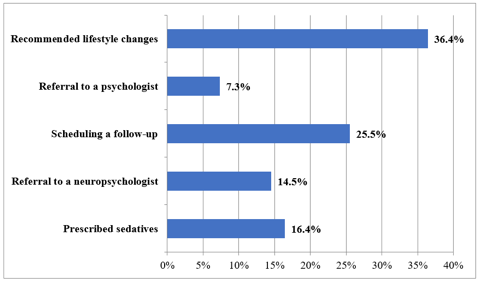

Figure 4: Anxiety interventions reported by general practitioners

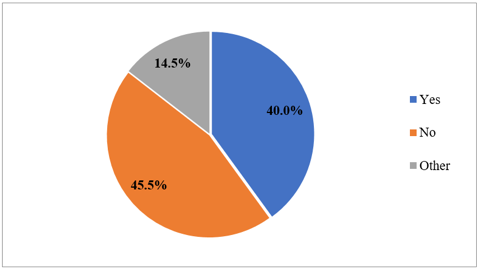

Figure 5: Feelings of competency recommending or prescribing antidepressants among general practitioners

R e s u l t s

Results indicated that most patients in our sample were older than 65 (89.1%). Anxiety and depressed mood were the two most frequently reported problems (Figure 1). Anxiety was most commonly reported in the population 18–50 years old (Figure 2). Psychological/psychiatric problems were most commonly identified during GPs’ interview with a patient by utilizing evidence-based behavioral health screening instruments (Figure 3).

Further, lifestyle changes were most commonly recommended in patients presenting with anxiety symptoms, followed by the scheduling of a follow-up visit for close monitoring (Figure 4). Overall, 45.5% of GPs did not feel comfortable prescribing antidepressant medications (Figure 5). Lastly, to increase competence in diagnosing and treating patients with psychological/psychiatric problems, 76.3% of GPs identified the need for additional educational opportunities that address prescribing psychotropic medications for depression, and 54.5% identified the need for topics related to initiating and managing antidepressant therapy.

D i s c u s s i o n

The most common psychological/psychiatric problems that GPs encounter in their practice are anxiety and depression. Most providers were routinely using screening instruments to diagnose depression (e.g., The Patient Health Questionnaire) as well as patient interviews. Depression was most prevalent in the youngest patient population, even though they were the least represented sample.

Several conclusions and recommendations can be drawn from our results. First, it is critical to be diligent when working with patients with mental health disorders and regularly using evidence-based screening instruments to look for signs and symptoms of anxiety and depression. This might help identify patients that require referral to a psychiatrist for treatment. In addition, about half of the GPs did not feel well equipped to treat depression or anxiety without consultation with a neuropsychiatrist. Consequently, GPs require increased education and training to promote their competence in prescribing psychotropic medications. We suggest exploring existing educational opportunities and making them available to GPs, including lectures given by neuropsychiatrists that are tailored to the needs of GPs with busy practices.

Conclusions

Outpatient GPs are often the first healthcare provider that assesses adults with mental health symptoms, which can be a challenge if they have very busy practices. Assisting GPs in screening and identifying patients with mental disorder might be beneficial. Providing education regarding antidepressant and antianxiety medications to GPs may increase their comfort in treating these disorders and decrease the need to refer to psychiatrists.

In addition, special consideration should be given to younger patient populations, who, according to our results, tend to present with prominent levels of depression and anxiety compared other age groups. When symptoms are detected, monitoring patient and offering longer follow-up visits might be helpful until refer to a psychiatrist is available. This study had some limitations, including a relatively small sample size and that the survey has not been validated. However, despite these limitations, our study indicates that additional education for GPs might provide long-term benefits for both patients and providers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to report.

Article Info

Article Type

Research ArticlePublication history

Received: Fri 08, Jun 2018Accepted: Tue 19, Jun 2018

Published: Sun 24, Jun 2018

Copyright

© 2023 Lidija Petrović-Dovat. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.PDR.2018.10.004

Author Info

Lidija Petrović-Dovat Nina Smiljanić Petrović-Bodor Olivera

Corresponding Author

Lidija Petrović-DovatDepartment of Psychiatry, Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania, USA

Figures & Tables

References

1. World Health Organization. Mental disorders–Fact sheet, April 2017, accessed 18.02.2018.

2. Wang PS, Aguilar‐Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, et al. (2007) Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Lancet 370: 841‐850. [Crossref]

3. Thornicroft G, Deb T, Henderson C (2016) Community mental health care worldwide: current status and further developments. World Psychiatry 15: 276-286. [Crossref]

4. World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2014, 2015.

5. Klemenc-Ketiš Z, Kersnik J, Tratnik E (2009) The presence of anxiety and depression in the adult population of family practice patients with chronic diseases. Zdrav Var 48: 170-176.

6. Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, et al. (2010) Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent (NSC-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49: 980-989. [Crossref]

7. Žikić O, Tošić-Golubović S, Slavković V (2010) Quality of life of patients with unipolar depression. Medicinski Pregled 63: 113-116.

8. Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S (2014) Risks of all-cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry 13: 153-160. [Crossref]

9. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG (2015) Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 72: 334-341. [Crossref]

10. World Health Organization. Suicide: Key Facts.

11. DE Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Cohen D, et al. (2011) Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry 10: 52-77. [Crossref]

12. Petrovic-Dovat L, Waxmonsky J, Iriana S, Fogel B, Zeiger T, et al. (2016) Development of integrated mental health services within pediatric ambulatory settings across an academic medical center. International J Integrated Care 16.

13. Petrovic-Dovat L, Berlin C, Bansal PS, Fogel B (2018) Designing programs and educational opportunities to aid pediatricians in treating children with mental illness in an outpatient academic pediatric setting. J Psychology Psychiatry 2: 1-3.