Humiliation and Injustice: Most Frequent and Most Hurting Stressors in Psychosomatic Patients

A B S T R A C T

Background: Injustice and humiliation are negative life events which can raise strong emotions, including shame, feelings of inferiority and helplessness, embitterment, anger, vindictive feelings and even aggressive rumination and acting out. This can severely impair not only the affected person but also her or his environment. Aim of this study was to investigate the frequency and impact of humiliation and injustice in psychiatric- psychosomatic patients.

Methods: In a semi-structured interview, which followed the outlines of the WHO International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF), 102 inpatients from a department of behavioural medicine were asked about burdens in life. Additionally, patients filled in the “ICD-10 Symptom Rating”, the “ICF AT 50-Psych”, the “Beck Depression Inventory” and the “HEALTH-49”.

Results: The experience of humiliation was rated as strong or very strong by 70.6% of the patients, being the most frequent burden, followed by persistent stress (59.9%), and injustice (56.8%). Comparisons between patients who complained about injustice alone, humiliation alone, injustice and humiliation combined, and neither injustice or humiliation show that experiences of humiliation and injustice similarly and significantly impair psychological well-being.

Conclusion: Humiliation and injustice are most frequent and impairing negative life events in psychiatric-psychosomatic patients. They need proper recognition and treatment.

Keywords

Negative life events, embitterment, shame, anger, psychiatric-psychosomatic rehabilitation, clinical psychology

Introduction

Stressful and negative life events can evoke a broad spectrum of psychological reactions [1-10]. Very burdensome are social events, like offence, humiliation, being let down, discrimination, insults, unfair treatment, injustice and social exclusion [11, 12]. The term humiliation is used to describe an offense, but also an emotional response, characterized by feelings of inferiority, devaluation and loss of self-respect, and is associated with sadness, anger, anxiety, and shame, but also ideations of aggression and revenge [13-18]. Humiliation has been called a “hybrid emotion”, combining shame and anger, one characterized by an internal attribution of responsibility and social withdrawal, and the other by “anger and aggression”, two outwardly directed emotions [13, 17]. The vivid association between the emotional event and situational characteristics of trauma can cause intrusive memories, which trigger the same emotions as have been experienced during the initial incident [13, 19-25].

When humiliation is associated with helplessness and hopelessness, an additional emotion can be embitterment. It has been described as a “last resort emotion” when the person feels cornered and does see no way out but defence under acceptance of self-destruction [26-28]. It can lead to dysfunctional behaviour in many areas of life, like social withdrawal, phobic avoidance, aggression, and suicidality [27].

Humiliation and injustice have been studied in social psychology, but found little attention in clinical psychology and psychiatry. It can be assumed that their relevance in the development of psychological disorders and especially of chronic mental illness is presently underrated. The scientific literature suggests that humiliation and injustice are strongly associated to each other, can frequently be observed in the general population, have impressive negative consequences, and should therefore also be of importance in mental disorders. Aim of the present study has been to examine the frequency and impact of humiliation and injustice in psychiatric-psychosomatic inpatients, be it separately or in combination.

Material and Methods

I Sample

Patients were treated in a department of behavioural medicine. They were suffering from all kinds of non-psychotic psychological disorders. According to the ICD-10 symptom rating, 38.4% patients were suffering from a depressive disorder, 24.2% from an anxiety disorder, 9.1% from an obsessive-compulsive disorder, 9.1% from a somatoform disorder, and 5.1% from an eating disorder. They were admitted by health or pension insurance because of sick leave or endangered ability to work. Patients were on average 48.1 years old (SD=9.16), 53.5% were female, 16.2% had at least a high school degree, 59.6% were married, 80.8% held a job, 17.2% were unemployed, and 47,9 % were presently on sick leave.

II Instruments

i Burdens in Life

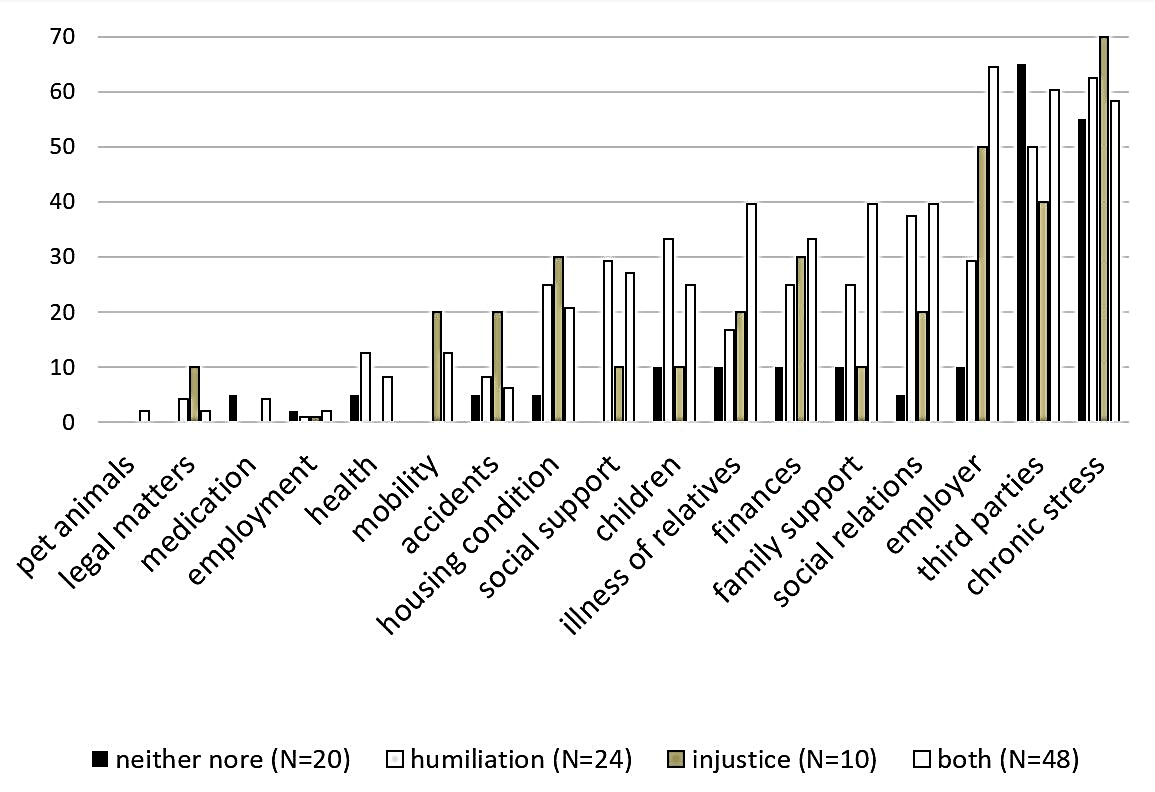

In a semi-structured interview, which followed outlines of the WHO International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF), patients were asked to make a rating on 20 life events using a five step Likert scale: “0=no burden at all”, “1 = mild burden” “2 = moderate burden”, “3 = severe burden, “4=very severe burden” (Figure 1). In the analyses only ratings of 3 and 4 were taken as “burdens”, indicating relevant burdens in contrast to daily hassles.

Ratings of 3 or 4 regarding humiliation and injustice allow to subclassify patients in those who complain about humiliation (H-group), injustice (I-group), humiliation and injustice (HI-group), and no respective problem (N-group).

ii Clinical Status

As part of the routine intake assessment patients filled in the “ICD-10 Symptom Rating” (ISR), a 29-item self-rating questionnaire, covering “depressive”, “anxiety”, “obsessive-compulsive”, “eating” and “somatoform” disorders [29].

The “ICF AT 50-Psych” is a self-rating scale to measure activity (A) and participation (T) in reference to the “International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health” (ICF), with the dimensions: “fulfil requirements”, “social relations and activities”, “verbal competency”, “fitness and well-being”, “closeness in relationships” and “social courtesy” [30, 31].

The “Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) is a 21 item self-rating instrument to measure the severity of depression [32]. The “HEALTH-49” has 49 items measuring “psychological and somatoform symptoms”, “psychological well-being”, “interactional problems”, “self-efficacy”, “activity and participation problems”, and “social support and burdens” [33]. The “Trier Bullying Scale” (TMKS) is a 12 item self-rating scale [34]. Sociodemographic characteristics (gender, marriage, school education, present work status, income) were taken from the routine intake assessment. This included a rating on the ability to work (“1=fully able” to “4=not able at all”).

Results

Analyses are based on 102 data sets. Figure 1 shows the percentage of severity ratings across all burdens. Most frequent were experiences of humiliation, with ratings 3 and 4 in 70.6% of patients, followed by complaints about persistent stress in 59.9%, experiences of injustice in 56.8%, interactional problems with third parties in 56,8%, problems with the employer in 44.2%.

Figure 1: Ratings of burdens in life (% patients).

There were 23.5% (N=24) of patients complaining about an experience of humiliation (H-group), 9.8% (N=10) only about injustice (I-group), 47.1% (N=48) about humiliation and injustice (HI-group), and 19.6% (N=20) about no burdens of this kind (N-group). These groups did not statistically differ in socio-demographic characteristics such as gender, marriage, school education, present work status, or income. H-patients were significantly (F(3,95)=3,49; p=0.02) older (M=52.96; SD=6.39) than HI-patients (M=45.81; SD=8.35).

Ability to work (mean value of ratings from “1=fully able” to “4=not able at all”), was significantly different (F(3,95)=3.16; p=0.03) between HI-patients (M=2.81; SD=0.96) and N-patients (M=2.11; SD=0.99). Figure 2 gives an overview of the percentage of complaints about other burdens for the four groups. HI-patients show the highest impairment rates across most other burdens, followed by I-patients. Areas in life, which are primarily associated with injustice, are related to the workplace and financial problems, like experiences with manager, living conditions, financial burden, permanent stress or legal problems. Humiliation is primarily associated with relations to others, like children, social relationships, family support, social support or other interactional factors.

Figure 2: Frequency of burdening contextual factors in dependence on humiliation and injustice (% of patients).

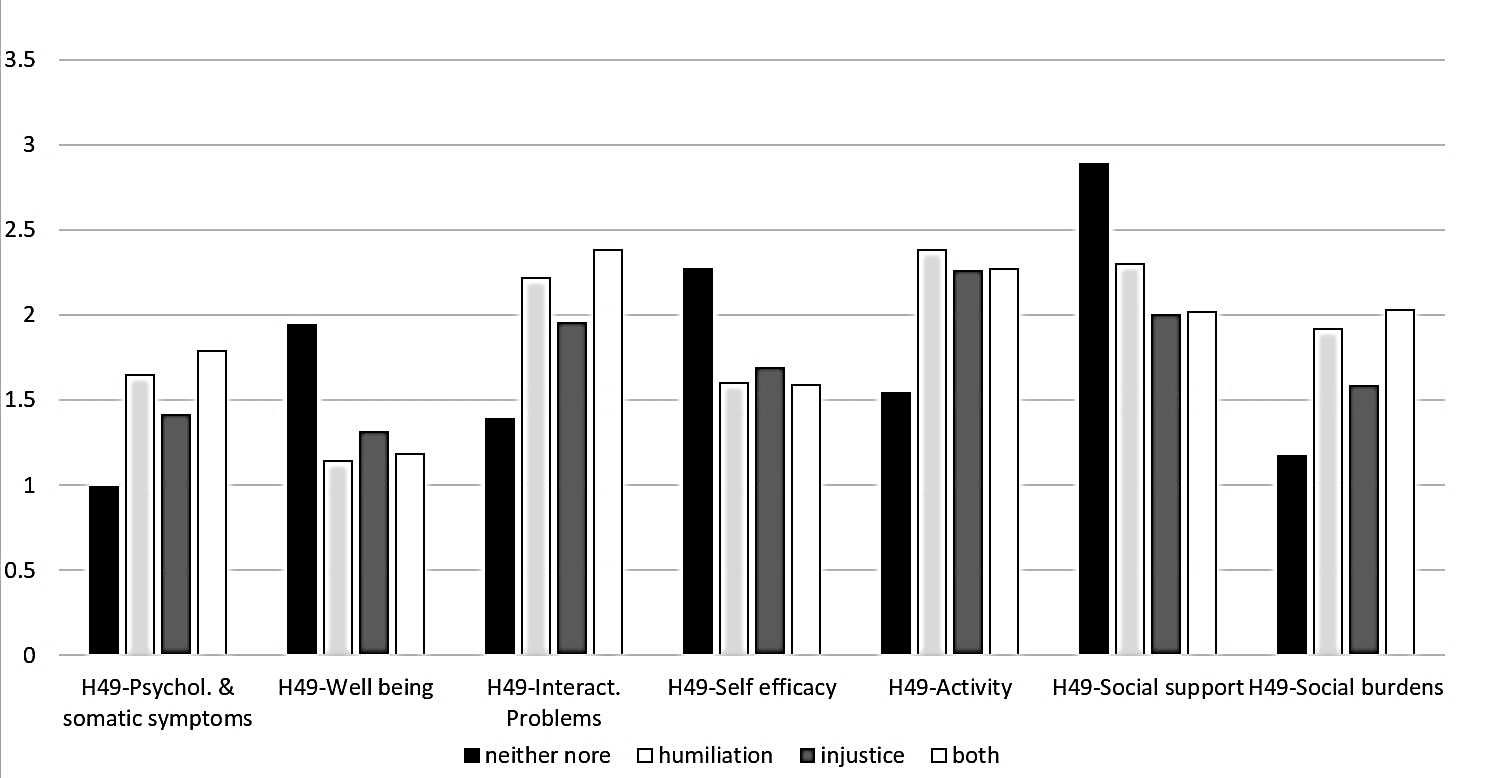

Figure 3 shows the results of the Health-49 questionnaire for the four patient groups. The ANOVA shows statistically significant differences between groups, which are due to comparisons of the H-, I-, and HI-groups with the N-group. Experiences of humiliation, be it alone or in combination with injustice have the strongest impact on the overall health status with significant differences in comparison to the N-group on “psychological and somatoform symptoms” (H: p=0.03; HI: p=0.001), “psychological well-being” (H: p<0.001; HI: p<0.001), “interactional difficulties” (H: p=0.02; HI: p<0.001), “activity and participation” (H: p=0.01; HI: p=0.001) and “social strain” (H: p=0.002; HI: p<0.001). Regarding “self-efficacy” (p=0.02) and “social support” (p=0.002) only the post-hoc tests for the HI-group have been significant.

Figure 3: Average scores of Health-49 subscales in dependence on humiliation and injustice experience. Statistical significant post-hoc tests refer to comparisons to the N-group (ANOVA: * p< .5, ** p< .01, *** p< .001).

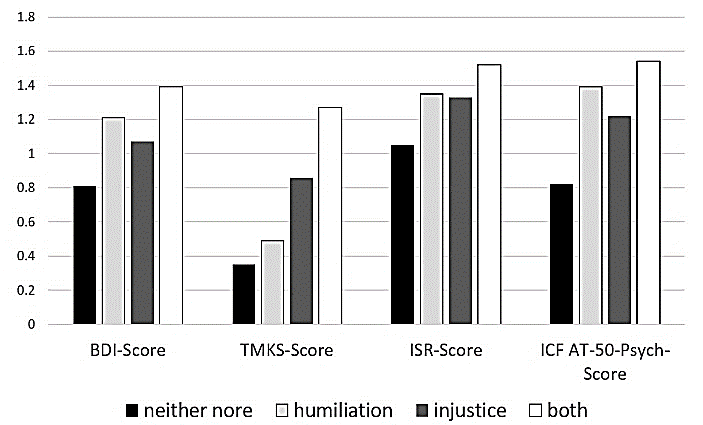

Figure 4 shows group comparisons for the BDI, TMKS, ISR, ICF AT-50. The ANOVA showed a significant difference across groups for the BDI (F(3,95)=5.62; p=0.001) due to the HI-group versus N-group (M=1.39, SD=0.53 vs. M=0.81, SD=0.46; p=0.001). The average TMKS Score was statistically significant across the groups (F(3,95)=5.69; p=0.001), due to the HI-group in comparison to N-group (M=1.27, SD=1.23 vs. M=0.35, SD=0.55; p<0.001). Also the difference between HI-group (M=1.27, SD=1.23) and the H-group (M=0.49, SD=0.54) was significant in the post-hoc test (p=0.002), meaning that humiliated patients had a lower average score of bullying experiences, comparable to the HI-group. For the ICF AT-50-Psych Score the ANOVA was significant (F(3,95)=4.45; p=0.01) for the HI-group (M=1.54, SD=0.73) in comparison to the N-group (M=0.82, SD=0.75). For the ISR-Score the ANOVA showed no significant differences.

Figure 4: Average scores of psychopathological scales in dependence on humiliation and injustice experience. Statistical significant post-hoc tests refer to comparisons to the N-group (ANOVA: * p< .5, ** p< .01, *** p< .001).

Discussion

The results of the present study allow several conclusions. In psychiatric-psychosomatic inpatients with mixed non-psychotic mental disorders and work-related problems, about two thirds of patients report burdensome and relevant humiliation and injustice. Half of all patients complain about a combination of both. Injustice can also be experienced as humiliating, and humiliation as injustice.

Nevertheless, there are experiences which only cause one or the other. The scientific literature suggests that humiliation is the result of social interactions [13, 17]. Victims feel degraded, insulted, shameful, and powerlessness [17]. This is supported by our data which show an association between humiliation and close social partners, like family, friends or other acquaintances. Injustice refers to a breach of rules or a violation of codes of conduct [35]. It is a problem especially at work and in other institutional contexts [36-39]. In this regard, unjustly treated patients in our study reported more often burdens in relation to the workplace, financial or legal problems. The different effects of humiliation and injustice are also reflected in the TMKS. Patients who report about humiliation show no increased rate of work-related conflicts in comparison to I-patients.

Another finding of our study is that both, humiliation and injustice, and even more so in combination, are associated with severe impairment in well-being and many-fold psychosomatic symptoms. The results confirm that humiliation and injustice lead to a complex and severely negative emotional state [13, 15-18].

These experiences can also result in strong problems of coping with daily demands and bear a high potential for either self or outward directed aggression [16, 40-47]. This is also shown by our results. Humiliated and unjustly treated patients feel burdened across most areas of life. As this is a cross sectional study we cannot prove any causality. Other studies on embitterment suggest that being let down, results in a general negative view of the world, causing a vicious circle [28]. Of interest is in this respect that HI-patients also were seen as less able to work.

In summary, the data show that experiences in injustice and humiliation are frequent problems in psychiatric-psychosomatic patients, associated with severe multiple negative consequences. Still, this is not recognized in the clinical field. A Medline search for “psych*” and “humiliation” in the titles of publications resulted in six papers only with no direct connection to mental or psychosomatic illness. For “injustice” there were eleven papers, one of which showing that injustice at work is related to an increased incidence of mental illness, and another which discusses that injustice in general is associated with more somatic pain [48, 49]. This state of affairs obviously is not sufficient.

Conclusion

The problem of injustice, humiliation, and embitterment must get much more attention in clinical practice and research. Clinical experience and preliminary scientific evidence suggest that these problems and patients are difficult to treat and may be in need of special interventions [27]. This conclusion can be drawn in spite of the limitations of the study. It is a cross sectional survey only, with no follow up information. It is coming from an inpatient group, which has been admitted because of problems with their ability to work. In spite of a standardized interview, the core data come from subjective patient reports.

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Funding

None.

Data Availability Statement

The data set can be requested from the Research Group Psychosomatic Rehabilitation (fpr@charite.de).

Article Info

Article Type

Research ArticlePublication history

Received: Sat 16, May 2020Accepted: Tue 28, Jul 2020

Published: Mon 24, Aug 2020

Copyright

© 2023 Michael Linden. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.PDR.2020.02.02

Author Info

Michael Linden Natalie Ida Bülau Franziska Kessemeier Axel Kobelt Markus Bassler

Corresponding Author

Michael LindenResearch Group Psychosomatic Rehabilitation, Charité University Medicine Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Figures & Tables

References

- Merih Altintas, Mustafa Bilici (2018) Evaluation of childhood trauma with respect to criminal behavior, dissociative experiences, adverse family experiences and psychiatric backgrounds among prison immates. Compr Psychiatry 82: 100-107. [Crossref]

- Tracy L Bale (2006) Stress sensitivity and the development of affective disorders. Horm Behav 50: 529-533. [Crossref]

- Boelen PA, Lensvelt Mulders GJML (2005) Psychometric properties of the grief cognition questionnaire. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 27: 291-303.

- Hoelterhoff M, Chung MC (2013) Death anxiety and well-being; Coping with life-threatening events. Traumatol 19: 280-291.

- Michael Linden, Kai Baumann, Barbara Lieberei, Max Rotter (2009) The Post-Traumatic Embitterment Self-Rating Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother 16: 139-147. [Crossref]

- Anthony D Mancini, George A Bonanno (2006) Resilience in the face of potential trauma: Clinical practices and illustrations. J Clin Psychol 62: 971-985. [Crossref]

- Saskia S L Mol, Arnoud Arntz, Job F M Metsemakers, Geert Jan Dinant, Pauline A P Vilters van Montfort et al. (2005) Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorders after non-traumatic events: Evidence from an open population study. Br J Psychiatry 186: 494-499. [Crossref]

- Müller Engelmann E, Dittman C, Weßlau C, Steil R (2016) Die Cognitive Processing Therapy-Cognitive Therapy Only zur Behandlung der komplexen Posttraumatischen Belastungsstörung. Verhaltensther 26: 195-203.

- T Ousdal, Q J Huys, A M Milde, A R Craven, L Ersland et al. (2018) The impact of traumatic stress on Pavlovian biases. Psychol Med 48: 327-336. [Crossref]

- Viinamäki H, Koskela K, Niskanen L, Taehkae V (1994) Mental adaptation to unemployment. Europ J Psychiatry 8: 243-252.

- Mathilde M Husky, Carolyn M Mazure, Viviane Kovess Masfety (2018) Gender differences in psychiatric and medical comorbidity with post-traumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry 84: 75-81. [Crossref]

- Rachel Sommer, Monika Bullinger, John Chaplin, Ju Ky Do, Mick Power et al. (2017) Experiencing health-related quality of life in paediatric short stature – a cross-cultural analysis of statements from patients and parents. Clin Psychol Psychother 24: 1370-1376. [Crossref]

- Coleman PT, Kugler K, Goldman JS (2007) The privilege of humiliation: The effects of social roles and norms on immediate and prolonged aggression in conflict. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association for Conflict Management 2007.

- Combs, DJY, Campbell G, Jackson M, Smith RH (2010). Exploring the consequences of humiliating a moral transgressor. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 32: 128-143.

- Jeremy Gingesa, Scott Atran (2008) Humiliation and the inertia effect: Implications for understanding violence and compromise in intractable intergroup conflicts. J Cogn Cult 8: 281-294.

- Hartling I, Luchetta T (1999) Humiliation: Assessing the impact of derision, degraduation and debasement. J Prim Prev 19: 259-274.

- Bernhard Leidner, Hammad Sheikh, Jeremy Ginges (2012) Affective Dimensions of Intergroup Humiliation. PLoS One 7: e46375. [Crossref]

- Lindner EG (2002) Healing the cycles of humiliation: How to attend to the emotional aspects of “unsolvable” conflicts and the use of “humiliation entrepreneurship”. Peace Confl J Peace Psychol 8: 125-138.

- S A Christianson (1984) The relationship between induced emotional arousal and amnesia. Scand J Psychol 25: 147-160. [Crossref]

- Christianson SA, Loftus EF (1987) Memory of traumatic events. Appl Cogn Psychol 1: 225-239.

- Christianson SA, Loftus EF (1990) Some characteristics of people´s traumatic memories. Bull Psychon Soc 28: 195-198.

- Christianson SA, Loftus, EF (1991) Remembering emotional events: The fate of detailed information. Cogn Emo 5: 81-108.

- S A Christianson, E F Loftus, H Hoffman, G R Loftus (1991) Eye fixations and remembering for emotional events. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 17: 693-701. [Crossref]

- J C Yuille, J L Cutshall (1986) A case study of eyewitness memory of a crime. J Appl Psychol 71: 291-301. [Crossref]

- Yuille JC, Cutshall JL (1989) Analysis of the statements of victims, witnesses and suspects. In: Yuille JC, editor. Credibility Assessment. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- J Alexander (1966) The psychology of bitterness. Int J Psychoanal 41: 514-520. [Crossref]

- Michael Linden, Kai Baumann, Barbara Lieberei, Constanze Lorenz, Max Rotter (2011) Treatment of posttraumatic embitterment disorder with cognitive behaviour therapy based on wisdom psychology and hedonia strategies. Psychother Psychosom 80: 199-205. [Crossref]

- Linden M, Maercker A (2011) Embitterment. Societal, psychological, and clinical perspectives. Wien: Springer.

- Karin Tritt, Friedrich von Heymann, Michael Zaudig, Irina Zacharias, Wolfgang Söllner et al. (2008) Entwicklung des Fragebogens “ICD-10-Symptom-Rating” (ISR). Z Psychosom Med Psychother 54: 409-418. [Crossref]

- Nosper M. ICF AT 50 Psych (2008) Entwicklung eines ICF-konformen Fragebogens für die Selbstbeurteilung von Aktivität und Teilhabe bei psychischen Störungen. DRV Schriften 77: 127-128.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2005) Internationale Klassifikation der Funktionsfähigkeit, Behinderung und Gesundheit (ICF). Genf: World Health Organization.

- Hautzinger M, Keller F, Kühner C (2006) Beck Depressions-Inventar II (BDI-II). Revision. Frankfurt a. M.: Pearson Assessment.

- Sven Rabung, Timo Harfst, Stephan Kawski, Uwe Koch, Hans Ullrich Wittchen et al. (2009) Psychometric analysis of a short form of the "Hamburg Modules for the Assessment of Psychosocial Health" (HEALTH-49). Z Psychosom Med Psychother 55: 162-179. [Crossref]

- Klusemann J, Nikolaides A, Schwickerath J, Brunn M, Kneip V (2008) Trierer Mobbing-Kurz-Skala (TMKS). Validierung eines Screening-Instrumentes zur diagnostischen Erfassung von Mobbing am Arbeitsplatz. Prax Klin Verhaltensmed Rehabil 82: 362-373.

- D T Miller (2001) Disrespect and the experience of injustice. Annu Rev Psychol 52: 527-553. [Crossref]

- Karatuna I, Gök S (2014) A study analyzing the association between Post-Traumatic-Embitterment Disorder and workplace bullying. J Workplace Behav Health 29: 127-142.

- I E H Madsen, S T Nyberg, L L Magnusson Hanson, J E Ferrie, K Ahola et al. (2017) Job strain as a risk factor for clinical depression: systematic review and meta-analysis with additional individual participant data. Psychol Med 47: 1342-1356. [Crossref]

- Evie Michailidis, Mark Cropley (2017) Exploring predictors and consequences of embitterment in the workplace. Ergonomics 60: 1197-1206. [Crossref]

- T Sensky, R Salimu, J Ballard, D Pereira (2015) Associations of chronic embitterment among NHS staff. Occup Med 65: 431-436. [Crossref]

- Brantlinger E (1993) Adolescent´s interpretation of social class influences on schooling. J Classr Interact 28: 1-12.

- G W Brown, T O Harris, C Hepworth (1995) Loss, humiliation and entrapment among women developing depression: A patient and non-patient comparison. Psychol Med 25: 7-21. [Crossref]

- J H Greist (1995) The diagnosis of social phobia. J Clin Psychiatry 56: 5-12. [Crossref]

- D C Klein (1991) The humiliation dynamic. An overview. J Prim Prev 12: 93-121. [Crossref]

- Rothenberg JJ (1994) Memories of schooling. Teaching Teacher Educ 10: 389-379.

- Darke JL (1990) Sexual aggression: Achieving power through humiliation. In: W. L. Marshall WL, Laws DR, Barabee HE, editors. Handbook of sexual assault: Issues, theories, and treatment of the offender (pp. 55-72). New York: Plenum Press p. 55-72.

- H Hendin (1994) Fall from power: Suicide of an executive. Suicide Life Threat Behav 24: 293-301. [Crossref]

- Hale R (1994) The role of humiliation and embarrassment in serial murder. Psychol J Hum Behav 31: 17-23.

- J E Ferrie, J Head, M J Shipley, J Vahtera, M G Marmot et al. (2006) Injustice at work and incidence of psychiatric morbidity: the Whitehall II study. Occup Environ Med 63: 443-450. [Crossref]

- Sullivan MJL, Scott W (2014) Perceived injustice and adverse recovery outcomes. Psychol Inj Law 7: 325-334.

- Bülau NI, Kessemeier F, Petermann F, Kobelt A (2016) Evaluation von Kontextfaktoren in der psychosomatischen Rehabilitation. Rehabil 55: 381-387.