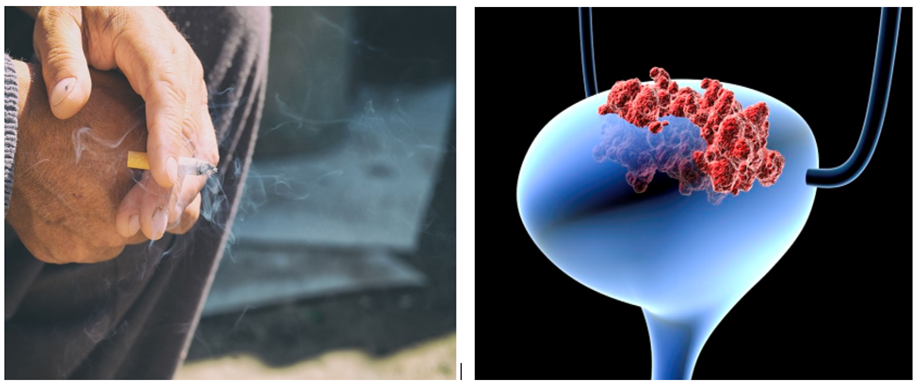

Smoking is the most common and important risk factor for bladder cancer. At least 3 times, smokers are as likely to get bladder cancer as compared to non-smokers. Smoking causes about half of all bladder cancer in both men and women. Smoking has been linked to the incidence of various malignancies. In western countries, at least 50% of bladder cancer diagnoses are due to smoking. Bladder cancer is the second-most common tobacco-related malignancy and attacks the lungs, and there is a relative risk of oral and upper gastrointestinal cancers between tobacco users and nontobacco users.

Cigarettes contain hydrocarbons, aromatic amines, 2-naphthylamine, and N-nitroso, which can damage DNA by forming bulky adducts and damaging single and multiple DNA chains and basal modification resulting in uncontrolled cell growth and inhibition of the tumor growth inhibitory mechanism. Carcinogens in cigarettes are generally metabolized by xenobiotic enzymes, such as N-acetyltransferase (NAT) and glutathione S-transferase. Carcinogens contained in cigarettes are excreted through the urine, so direct contact with the urinary tract occurs and increases the risk of malignancy. If any person has a slow NAT2 acetylation activity (generally found in smokers), there will be a reduction in the carcinogen detoxification efficiency as carcinogens accumulate in high levels of the urothelium.

Early lung cancer researchers focused mainly on the risk from cigarette smoking; more recent studies have shown the role of genetic susceptibility in lung cancer risk in case-control analyses. Smoking being the primary risk factor for bladder cancer, direct damage to the DNA by cigarette smoke toxins is unlikely to be the main reason for the forming cancers. The reason lying behind the fact is that – the smoke toxins accelerate other DNA damaging events and attention being focused on a family of enzymes called “APOBEC.” Enzymes APOBEC destroys the viruses by causing mutations in their DNA as part of the body’s natural defenses against infection, but recent studies suggest – they might mistakenly target human DNA in several cancer types. Numerous retrospective and prospective studies have clearly demonstrated a dose-related to the increased risk of lung cancer associated with cigarette smoking.