Relationship Between Religious Attitude and Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Symptoms in University Students in Iran

A B S T R A C T

A considerable proportion of young adults studying at universities have a mental disorder. Previous research has shown a negative relationship between various religiosity and psychopathology measures, with different strengths of this correlation depending on the religiosity measure. The aim of the present study is to investigate the strength of association between religious attitude and depression, anxiety and stress in Iranian university students. Thirty-three students from two Iranian universities filled in the Religious Attitude Scale for University Students (RASUS), the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-42). Religious attitude correlates negatively with all psychopathological variables with a moderate effect size (e.g., with BDI-II: r = -.47; p = .006). When dividing the sample in low vs. high religious people, there were significantly more students without depression symptoms in the high religious attitude group than in the low group.

Keywords

Religious attitude, anxiety, depression, stress, students

Introduction

A considerable proportion of young adults studying at universities have a mental disorder. US-American college students exhibit a prevalence of 20.0% for depression and 24.3% for anxiety disorders, 16.5% for both depression and anxiety (American College Health Association, 2019). This is higher than in the general population when compared with the results of a meta-analysis [1]. In the same study, 13.4% of the students reported having tremendous stress and 45.3% had more than average stress.

The situation is similar for Iranian university students. A recent meta-analysis on depression, anxiety and stress symptoms using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) as an assessment tool found higher mean values in Iranian university students than comparable studies in Western countries [2, 3]. The reason might be that mental disorders are even more stigmatising in this Muslim country than in Western countries, which keeps students from seeking help [4].

Mental disorders in university students might have several negative consequences, including poor academic achievement, social problems, increased rates of substance use and suicide. At the same time, early adulthood is a phase of life that involves a number of challenges, e.g., moving from home to another city, decreasing parental support, increasing a new peer support system, and academic challenges etc.

Religiosity and Mental Health

Iran is a country in which religion plays a major role in most areas of life. Therefore, adolescents and young adults are influenced by religious attitudes and activities of their families and religious communities. Research that has been conducted mainly in the USA and Europe has shown that the adaptive development of adolescents and adults are positively associated with religious measures [5, 6]. In their extensive meta-analysis on the relationship between various religiosity and mental health measures, they found an overall correlation of r = 0.10, regardless of the specific religiosity or mental health definition, indicating a small, but positive association. However, when differentiating between several religiosity measures, they found that studies focusing on social and behavioural aspects of religion (e.g., participating in religious, social activities) show only zero (or negative) associations, whereas studies focusing on religious beliefs and attitudes as well as studies focusing on personal devotion found positive and stronger associations. A recent overview of more than a hundred meta-analyses and systematic reviews concluded that “the case for causal influence may now be compelling, and in most cases [religiosity/spirituality] … involvement is associated with better health, although negative associations also exist” (p. 261) [7].

There are also studies on student samples showing that religious and spiritual measures are positively related to mental wellbeing and life satisfaction [8]. Also, several longitudinal studies investigating the impact of religiosity on mental health have been published. In a recent meta-analysis, the prospective correlation of religiosity with mental health was positive, but small (r =.08) [9]. One of the most important religiosity components contributing to mental health was the personal importance of religion in this meta-analysis.

Muslim Religiosity and Mental Health

The question arises as to whether this positive relationship between religiosity and mental wellbeing can also be found in Muslim countries because there might be cross-cultural differences. For example, Iranian students were shown to have higher scores on several religiosity scales than Austrian student, and students in Kuwait more so than in the USA [10-12]. Interestingly, Iranian students have even higher scores on several religiosity measures than older Iranian people [13]. There are studies from various Muslim countries showing that Muslim religiosity is positively associated with mental health and negatively associated with psychopathology. The samples of these studies include adolescents in Egypt, adolescents in Kuwait, adults in Algeria, college students in Algeria, and college students in Kuwait [11, 12, 14-20].

To the best of our knowledge, there are only two internationally published articles on the religiosity-mental health relationship in Iranian samples, both with samples of university students. Abdel-Khalek et al. indicate that there are additional unpublished studies and studies published in Arabic or Farsi [21]. One of the internationally published articles used a scale that they developed for this study, which measures positive and negative spiritual experiences [22]. They found that psychopathology such as depression and anxiety was negatively correlated with positive spiritual experiences, but positively with negative spiritual experiences. The second study used a scale to measure extrinsic and intrinsic religious orientation and found a negative correlation with depression [23, 24].

There is no study, to the best of our knowledge, on religious attitude and its association with mental health in Iran. The term “attitude” refers to one of the most important constructs in social psychology. Ajzen defined it: “There is general agreement that attitude represents a summary evaluation of a psychological object captured in such attribute dimensions as good-bad, harmful-beneficial, pleasant-unpleasant, and likable-dislikable…” (p. 28) [25]. It has been argued by Francis that the measurement of religious attitude is superior to religious affiliation, beliefs, and practices because it is better able to indicate individual differences in religiosity [26]. He argues that religious affiliation as indicating one’s belonging to a certain religious tradition is too superficial to be a reliable measure. Religious beliefs might be only convictions and do not correspond to the actual personal religious life of an individual. Also, the measurement of religious practices might be difficult because personal and social constraints can inhibit or modify such practices.

Many studies have used the “Francis Scale of Attitude toward Christianity” (FSAC) to examine a wide range of correlates of religiosity during childhood, adolescence and adulthood [26, 27]. The direct translation of the FSAC in the Muslim context suffers from problems with content and context validity [28]. Scales that have been developed for the Muslim context include the “Religious Attitude Scale for University Students” (RASUS) and the “Ok-Religious Attitude Scale” [29, 30]. Studies using the RASUS found positive associations between religious attitude and, for example, a secure attachment in college students, emotional maturity in student teachers and positive attitude to the hijab, the women’s headwear [31-33]. However, there is no published study on the association between Muslim religious attitudes and mental health in Iranian university students.

Aim of the Present Study

The aim of the present study is (1) to investigate the strength of association between religious attitude and depression, anxiety and stress in Iranian university students and (2) to investigate the frequencies of the categories of depression (no, mild, moderate, and severe depression) in low vs. high religious students.

Methods

I Participants

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The participants were recruited in 2019 from two universities in Iran, Gachsaran University and Yasuj University. Eligible participants were students at one of the participating universities, aged 18 or older (M = 23.5, SD = 2.26; 80% female). 33 students were included in the study after they had given their consent to participate. Some of the participants lived in urban surroundings, some in rural areas. All of them were religious Muslims.

II Measures

i Religious Attitude Scale for University Students (RASUS)

The Religious Attitude Scale for University Students (RASUS) was designed by Krishnaraj and Balasubramanian from the University of Alagappa, India [29]. The aim of the questionnaire was to measure students’ attitudes towards religion. It consists of 34 questions with a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. Some items are reversely coded. Sample items are: “Religion helps to develop the optimistic spirit”; “Religion teaches one to love all in the world”; “Religion promotes man’s inner discipline”; “Religion makes people irrational” (negatively scored). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94 in the present sample. The retest reliability hast shown to be r = .87, internal validity r = .65 with the religious scale from the Allport-Vernon-Lindzey Study of Values [29].

ii Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II)

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report inventory that assesses symptoms of depression in the previous seven days [34]. Each item is rated from 0 to 3 according to the severity of difficulty experienced; total scores range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more depression. The BDI-II has been shown to have good psychometric properties in psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations in various countries. We used the Persian (Farsi) translation of the BDI-II, which was developed by repeated translation and back-translation of the original questionnaire [35]. In an Iranian student sample with 9.5% fulfilling the DSM-IV diagnosis of a Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), the BDI-II cut-off point of 22 or greater was the most suitable to screen MDD, whereas for screening milder but clinically significant depression, the cut-off point of 14 or greater was the best [36]. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88 in the present sample.

iii Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-42)

The DASS-42 is a 42-item self-report inventory that assesses symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress in the previous seven days [2]. The depression subscale includes items evaluating symptoms such as anhedonia, feelings of sadness, worthlessness, hopelessness, and lack of energy. The anxiety subscale includes items evaluating physiological arousal, phobias, and situational anxiety. The stress subscale includes items evaluating symptoms such as difficulty in achieving relaxation, state of nervous tension, agitation, overreaction to situations, irritability, and restlessness. Each item is rated from 0 to 3 according to the severity or frequency of the symptom. Each subscale has 14 items, and a participant’s score in each subscale is obtained by the sum of all items related to a subscale.

The DASS-42 has been shown to have good psychometric properties in psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations in various countries, and the three-factor structure has also been approved. We used the Persian (Farsi) translation of the DASS-42 [37]. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.92 for depression, 0.87 for anxiety and 0.92 for stress in the present sample.

III Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Pearson correlations between the variables were calculated to assess their associations. The sample was divided into two groups with regard to religious attitude (after median dichotomization) and into three groups with regard to depression severity (no, mild, and moderate depression according to published cut-offs).

Results

Mean religious attitude score is M = 123.88 (SD = 21.09). Mean values for depression, anxiety, and stress are presented in (Table 1). The correlations of religious attitude with depression, anxiety, and stress are presented in (Table 1). Religious attitude correlates negatively with all psychopathological variables with a moderate effect size. The correlation is significant for depression using the BDI-II (r = -.47; p = .006), for depression using the DASS-42 (r = -.35; p = .049), for anxiety (r = -.45; p = .008), for stress (r = -.39; p = .024), and DASS-42 total score (r = -.42; p = .015).

Table 1: Correlations of religious attitude with

psychopathology (N = 33).

|

Variables |

M (SD) |

r |

p |

|

Depression (BDI-II) |

12.58 (9.54) |

-.47** |

.006 |

|

Depression (DASS-42) |

14.15 (10.38) |

-.35* |

.049 |

|

Anxiety (DASS-42) |

12.79 (8.29) |

-.45** |

.008 |

|

Stress (DASS-42) |

21.15 (10.71) |

-.39* |

.024 |

|

Total Symptoms (DASS-42) |

48.09 (27.45) |

-.42* |

.015 |

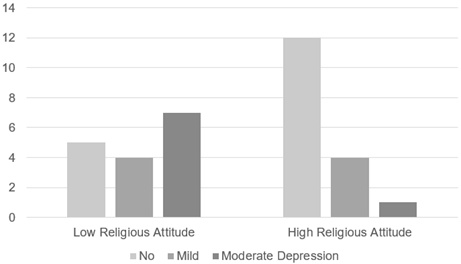

The participants were divided into three subgroups for their severity of depression values: 51.5% with no symptoms, 24.2% with mild symptoms, and 24.2% with moderate symptoms of depression (Table 2). Two subgroups with regard to religious attitude (low, and high) were compared for their depression severity. There were significantly more students without depression symptoms in the high religious attitude group than in the low group (Chi2 = 7.36, p = .025). Figure 1 depicts this association.

Figure 1: High vs. low religious attitude by categories of depression (N = 33).

Table 2: High vs. low religious attitude by categories of

depression (N = 33).

|

Religious Attitude |

Categories of Depression |

||

|

|

No |

Mild |

Moderate |

|

Low |

31.3% |

25.0% |

43.8% |

|

High |

70.6% |

23.5% |

5.9% |

|

Total group |

51.5% |

24.2% |

24.2% |

Chi2 =

7.36, p = .025

Discussion

In a sample of university students in Iran, we found negative correlations between religious attitude with depression, anxiety, and stress that were statistically significant or highly significant. When dividing the sample into subgroups with regard to the severity of depression, significantly more students without depression symptoms were found in the high religious attitude group than in the low group.

I Comparison with Other Studies on the Association of Religiosity with Mental Health

The RASUS score of M = 123.88 (SD = 21.09) is similar to that obtained in the study of Meenatchii and Benjamin with M = 119.7 (SD = 31.64), which also used a student sample [32]. The BDI-II score in the current study was higher than in the original validation study of the Persian version, which also used an Iranian student sample: M = 12.58 (SD = 9.54) vs. 9.79 (SD = 7.96) [35]. The DASS is usually used in its 21-item version in Iran; therefore, we compare our results of the DASS-42 with a Turkish sample of university students. The scores in our sample were higher than in the study of Demirbatir: for depression M = 14.15 (10.38) vs. 12.24 (SD = 9.52), for anxiety M = 12.79 (8.29) vs. 11.67 (SD = 8.74), and for stress M = 21.15 (10.71) vs. 16.86 (SD = 9.38) [38]. This might – at least in part – be a consequence of the enduring economic sanctions on Iran that obviously also impact the stress level and mental health of Iranian citizens [39, 40].

The correlation between religious attitude and psychopathological variables found in the present study was moderate, between -.35 and -.47. These are higher than in a study with students in Kuwait (-.23) and much higher than those aggregated in meta-analyses that are typically around -.10 [6, 7, 12]. There might be several reasons. First, the measure of religious attitude used in this study might be more relevant for mental health than many other religiosity scales [26]. Second, the psychopathological variables (BDI-II and DASS-42) might be more responsive to religious attitudes than life satisfaction or other general well-being scales [6]. Third, Iran is a country where religion affects all areas of life and where religiosity has high importance. The relative importance of religiosity might increase the religiosity-mental health associations.

II Mechanisms of this Association

The question of which (causal) mechanism underlies the negative association between religious attitude and depression, anxiety, and stress is certainly one of the most important questions for future research. In principle, the association can be either due to a causal effect of religiosity on mental health, or due to a causal effect of mental health on religiosity, or due to common factors influencing both religiosity and vulnerability to psychopathology [41].

With regard to a causal effect of religiosity on mental health, several possible mechanisms have been proposed and researched for a potential causal effect of religiosity on mental health. Social support, which is known as a buffer against stress, is often associated with the religious community and might be responsible for the positive effect of religiosity on health [42]. Involvement in this religious community gives individuals a sense of belonging [43]. Religiosity also gives individuals hope and a sense of meaning and purpose in life, which is, in turn, associated with mental health [44, 45]. In addition, self-transcendent positive emotions such as awe, gratitude and peace might be mediators of the association between religiosity and mental health [46]. Furthermore, religious virtues such as self-control, forgiveness and altruism might also mediate this association [47, 48].

With regard to a causal effect of mental health on religiosity, depression, anxiety and other psychopathological syndromes might affect religiosity in a negative way. For example, depression associated with loss of interest in previously pleasurable activities might also lead to withdrawal from religious activities [49]. For others, the reverse process might be true, i.e., some individuals might seek comfort in their religion in response to mental illness [50].

Finally, genetic and environmental factors might be common factors that underlie both religiosity and vulnerability to psychopathology. For example, parental modelling and attachment styles might influence religious development and at the same time, personal resources, which reduce the vulnerability to mental disorders [41]. However, research accumulates evidence that the heritable contribution of religiosity is rather distinct from depression, suggesting that there are no common genetic factors for religiosity and depression [51]. Longitudinal studies with a larger number of potential variables are needed in order to disentangle the various potential mechanisms behind the religiousness-mental health association.

III Limitations

There are some limitations to this study that should be considered in the interpretation of the results. First, this is a cross-sectional study; thus, no causal inferences on the religiosity-mental health association can be made. Second, we used only one religiosity variable. We are convinced that religious attitude is one of the best religious predictors of mental health; however, we cannot conclude its relative importance unless other religious variables such as religious activities and devotion are also used. Third, only the presence of depression, anxiety, and stress was investigated. Measures of positive wellbeing, as well as psychiatric diagnoses, have not been applied. Forth, potential mediating variables such as social support, sense of meaning in life, hope, gratitude, self-control, and forgiveness, among others, were not used. Future studies should address the role that other variables may have in this association in a longitudinal study. Fifth, this would necessitate a larger sample than 33 as in the present study. Sixth, the sample consists of university students, but not other young adults with a different working careers and no other age groups in Iran. Therefore, we cannot generalize our results to other Iranian or Muslim populations.

IV Practical Consequences for the Treatment

Based on our finding that religiosity is negatively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress, religious and spiritual themes (such as guilt and forgiveness) and practices (such as prayer and meditation) can be added to the standard psychotherapy. It has been suggested tailoring the treatment to the patient’s values improves the efficacy [52]. Religious patients usually want to discuss spiritual issues in psychotherapy [53]. Therefore, psychotherapists should be sensitive to the patient’s spiritual issues and also to the inclusion of interventions that may be in conflict with the patient’s beliefs.

In a review of the effects of religion-accommodative psychotherapy for depression and anxiety, six studies incorporated the intervention with a Christian perspective, and five with an Islamic perspective [54]. Cognitive therapy (CT) was the secular control intervention in most of these studies. The studies showed that religion-accommodative psychotherapy was an effective treatment for patients with anxiety or depression, with outcomes equivalent, although not superior to the control CT interventions. In addition, results suggest that religion-accommodative cognitive therapy is more effective than secular CT for highly religious individuals. A more recent meta-analysis found similar results on Christian, Muslim, Jewish and Taoist adaptations of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) [55].

What are the aspects of religiosity and spirituality that are included in these religion-accommodative psychotherapies? Anderson et al. mention the following strategies in their meta-analysis [55]:

i. “Discussion of religious teachings or scriptures as supportive evidence to counter irrational thoughts or to support cognitive or behavioural change;

ii. Use of positive religious or spiritual coping techniques (for example, applying scriptural or spiritual solutions to the psychological problems of fear, anger, guilt, shame or despair);

iii. Promotion of helpful belief or value systems, or use of shared value systems to strengthen therapeutic relationships;

iv. Incorporation of religious practices such as prayer” (p. 187).

Informed Consent

The objectives and goals and detailed information about the assessment were explained to the participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Islamic Azad University of Gachsaran, Iran.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, SF, upon reasonable request.

Article Info

Article Type

Research ArticlePublication history

Received: Thu 09, Jun 2022Accepted: Fri 01, Jul 2022

Published: Fri 29, Jul 2022

Copyright

© 2023 Simon Forstmeier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Hosting by Science Repository.DOI: 10.31487/j.PDR.2022.01.02

Author Info

Shapour Fereydouni Samira Fereidouny Doshmanzeiary Simon Forstmeier

Corresponding Author

Simon ForstmeierDepartment of Psychology, Developmental Psychology and Clinical Psychology of the Lifespan, University of Siegen, Siegen, Germany

Figures & Tables

Table 1: Correlations of religious attitude with

psychopathology (N = 33).

|

Variables |

M (SD) |

r |

p |

|

Depression (BDI-II) |

12.58 (9.54) |

-.47** |

.006 |

|

Depression (DASS-42) |

14.15 (10.38) |

-.35* |

.049 |

|

Anxiety (DASS-42) |

12.79 (8.29) |

-.45** |

.008 |

|

Stress (DASS-42) |

21.15 (10.71) |

-.39* |

.024 |

|

Total Symptoms (DASS-42) |

48.09 (27.45) |

-.42* |

.015 |

Table 2: High vs. low religious attitude by categories of

depression (N = 33).

|

Religious Attitude |

Categories of Depression |

||

|

|

No |

Mild |

Moderate |

|

Low |

31.3% |

25.0% |

43.8% |

|

High |

70.6% |

23.5% |

5.9% |

|

Total group |

51.5% |

24.2% |

24.2% |

Chi2 =

7.36, p = .025

References

1.

Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW

et al. (2014) The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic

review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol 43: 476-493. [Crossref]

2.

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. 2nd ed. Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

3.

Mohammadzadeh J, Mami S, Omidi K (2019) Mean Scores

of Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Iranian University Students Based on

DASS-21: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol Res 6:

42-48.

4.

Taghva A, Farsi Z, Javanmard Y, Atashi A, Hajebi A

et al. (2017) Strategies to reduce the stigma toward people with mental

disorders in Iran: stakeholders’ perspectives. BMC Psychiatry 17: 17. [Crossref]

5.

Wright LS, Frost CJ, Wisecarver SJ (1993) Church

attendance, meaningfulness of religion, and depressive symptomatology among

adolescents. J Youth Adolescence 22: 559-568.

6.

Hackney CH, Sanders GS (2003) Religiosity and

Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Studies. J Scientific Study

Religion 42: 43-55.

7.

Oman D, Syme SL (2018) Weighing the Evidence: What

Is Revealed by 100+ Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of

Religion/Spirituality and Health? In: Oman D, editor. Why Religion and

Spirituality Matter for Public Health: Evidence, Implications, and Resources

[Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing 261-281.

8.

Zullig KJ, Ward RM, Horn T (2006) The Association

Between Perceived Spirituality, Religiosity, and Life Satisfaction: The

Mediating Role of Self-Rated Health. Soc Indic Res 79: 255.

9.

Garssen B, Visser A, Pool G (2021) Does

Spirituality or Religion Positively Affect Mental Health? Meta-analysis of

Longitudinal Studies. Int J Psychol Religion 31: 4-20.

10. Bahrami F, Dadfar M, Unterrainer HF, Zarean M, Mahmood Alilu M (2015)

Intercultural dimensions of religious spiritual well-being in college students.

Int J Biol Pharm Allied Sci 4: 4053-4069.

11. Abdel Khalek AM, Lester D (2007) Religiosity, health, and psychopathology

in two cultures: Kuwait and USA. Mental Health Religion Culture 10:

537-550.

12. Abdel Khalek AM, Lester D (2012) Constructions of religiosity,

subjective well-being, anxiety, and depression in two cultures: Kuwait and USA.

Int J Soc Psychiatry 58: 138-145. [Crossref]

13. Dadfar M, Lester D, Turan Y, Beshai JA, Unterrainer HF (2021) Religious

spiritual well-being: results from Muslim Iranian clinical and non-clinical

samples by age, sex and group. J Religion Spirituality Aging 33: 16-37.

14. Abdel Khalek AM, Korayem AS, Lester D (2021) Religiosity as a predictor

of mental health in Egyptian teenagers in preparatory and secondary school. Int

J Soc Psychiatry 67: 260-268. [Crossref]

15. Abdel Khalek AM (2007) Religiosity, happiness, health, and

psychopathology in a probability sample of Muslim adolescents. Mental Health

Religion Culture 10: 571-583.

16. Abdel Khalek AM (2011) Religiosity, subjective well-being, self-esteem,

and anxiety among Kuwaiti Muslim adolescents. Mental Health Religion Culture

14: 129-140.

17. Baroun KA (2006) Relations among religiosity, health, happiness, and

anxiety for Kuwaiti adolescents. Psychol Rep 99: 717-722. [Crossref]

18. Tiliouine H (2009) Measuring Satisfaction with Religiosity and Its

Contribution to the Personal Well-Being Index in a Muslim Sample. Applied

Research Quality Life 4: 91-108.

19. Tiliouine H, Cummins RA, Davern M (2009) Islamic religiosity,

subjective well-being, and health. Mental Health Religion Culture 12:

55-74.

20. Abdel Khalek AM, Naceur F (2007) Religiosity and its association with

positive and negative emotions among college students from Algeria. Mental

Health Religion Culture 10: 159-170.

21. Abdel Khalek AM, Nuño L, Gómez Benito J, Lester D (2019) The

Relationship Between Religiosity and Anxiety: A Meta-analysis. J Relig

Health 58: 1847-1856. [Crossref]

22. Ghobary Bonab B, Hakimirad, Habibi (2010) Relation between mental

health and spirituality in Tehran University student. Procedia Social

Behavioral Sciences 5: 887-891.

23. Tahmasbipour N, Taheri A (2011) The Investigation of Relationship

between Religious Attitude (Intrinsic and Extrinsic) with depression in the

university students. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 30:

712-716.

24. Allport GW, Ross JM (1967) Personal religious orientation and

prejudice. J Pers Soc Psychol 5: 432-443. [Crossref]

25. Ajzen I (2001) Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu Rev Psychol

52: 27-58. [Crossref]

26. Francis LJ (2009) Understanding the Attitudinal Dimensions of Religion

and Spirituality. In: de Souza M, Francis LJ, O’Higgins-Norman J, Scott D,

editors. International Handbook of Education for Spirituality, Care and

Wellbeing [Internet]. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands 147-167.

27. Francis LJ (1989) Measuring attitude towards Christianity during childhood

and adolescence. Personality Individual Differences 10: 695-698.

28. Sahin A, Francis LJ (2002) Assessing Attitude toward Islam among Muslim

Adolescents: The Psychometric Properties of the Sahin-Francis Scale. Muslim

Education Quarterly 19: 35-47.

29. Fatemi A, Sepanta M, Nosrati N, Khaledian M (2014) The relationship of

the emotional intelligence and Self-esteem with religious attitudes among the

students. Int J Basic Sciences Applied Res 3: 186-192.

30. Ok Ü (2016) The Ok-Religious Attitude Scale (Islam): introducing an

instrument originated in Turkish for international use. J Beliefs Values

37: 55-67.

31. Karami Baghteyfouni T, Nemati Sogolitappeh F, Karami Baghteyfouni Z,

Raaei F, Sharbafzadeh A (2015) The Relationship between Attachment Lifestyle

with religious attitudes and anxiety. Int J Sci Management Development

3: 993-997.

32. Meenatchii B, Benjamin EW (2013) Religious Attitude and Emotional

Maturity of Student Teachers in Puducherry Region. Indian J Appl Res 3:

60-61.

33. Nemati Sogolitappeh F, Karami Baghteyfouni Z, Raaei F, Khaledian M

(2017) Relation of religious attitude and hijab with happiness among married

women. World Scientific News 72: 407-418.

34. Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W (1996) Comparison of Beck

Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Personality

Assessment 67: 588-597.

35. Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N (2005)

Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression

Inventory-Second edition: BDI-II-Persian. Depress Anxiety 21: 185-192. [Crossref]

36. Vasegh S, Baradaran N (2014) Using the Persian-language version of the

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II-Persian) for the screening of depression

in students. J Nerv Ment Dis 202: 738-744. [Crossref]

37. Afzali A, Delavar A, Borjali A, Mirzamani M (2007) Psychometric

properties of DASS-42 as assessed in a sampel of kermanshah high school

students. J Res Behavioural Sciences 5: 81-92.

38. Demirbatir RE (2012) Undergraduate Music Student’s Depression, Anxiety and

Stress Levels: A Study from Turkey. Procedia Social Behavioral Sciences

46: 2995-2999.

39. Kokabisaghi F, Miller AC, Bashar FR, Salesi M, Zarchi AAK et al. (2019)

Impact of United States political sanctions on international collaborations and

research in Iran. BMJ Glob Health 4: e001692. [Crossref]

40. Aloosh M, Salavati A, Aloosh A (2019) Economic sanctions threaten

population health: the case of Iran. Public Health 169: 10-13. [Crossref]

41. Smith TB, McCullough ME, Poll J (2003) Religiousness and depression:

Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life

events. Psychol Bull 129: 614-636. [Crossref]

42. Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB (2012) Handbook of religion and

health. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

43. Krause N, Hayward RD (2013) Religious Involvement and Feelings of

Connectedness with Others among Older Americans. Arch Psychol Religion

35: 259-282.

44. Steger MF, Frazier P (2005) Meaning in Life: One Link in the Chain From

Religiousness to Well-Being. J Counseling Psychol 52: 574-582.

45. Aghababaei N, Sohrabi F, Eskandari H, Borjali A, Farrokhi N et al.

(2016) Predicting subjective well-being by religious and scientific attitudes

with hope, purpose in life, and death anxiety as mediators. Personality

Individual Differences 90: 93-98.

46. Van Cappellen P, Toth Gauthier M, Saroglou V, Fredrickson BL (2016)

Religion and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Positive Emotions. J

Happiness Stud 17: 485-505.

47. McCullough ME, Willoughby BLB (2009) Religion, self-regulation, and

self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychol Bull

135: 69-93. [Crossref]

48. Sharma S, Singh K (2019) Religion and Well-Being: The Mediating Role of

Positive Virtues. J Relig Health 58: 119-131. [Crossref]

49. Maselko J, Hayward RD, Hanlon A, Buka S, Meador K (2012) Religious Service

Attendance and Major Depression: A Case of Reverse Causality? Am J Epidemiol

175: 576-583. [Crossref]

50. Ferraro KF, Kelley Moore JA (2000) Religious consolation among men and

women: Do health problems spur seeking? J Scientific Study Religion 39:

220-234.

51. Anderson MR, Miller L, Wickramaratne P, Svob C, Odgerel Z et al. (2017)

Genetic Correlates of Spirituality/Religion and Depression: A Study in

Offspring and Grandchildren at High and Low Familial Risk for Depression. Spiritual

Clin Pract (Wash D C ) 4: 43-63. [Crossref]

52. Sotsky SM, Glass DR, Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Collins JF et al. (1991)

Patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: Findings

in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am J

Psychiatry 148: 997-1008. [Crossref]

53. Rose EM, Westefeld JS, Ansley TN (2008) Spiritual issues in counseling:

Clients’ beliefs and preferences. J Counseling Psychol 48: 61-71.

54. Paukert AL, Phillips LL, Cully JA, Romero C, Stanley MA (2011) Systematic Review of the Effects of Religion-Accommodative Psychotherapy for Depression and Anxiety. J Contemp Psychother 41: 99-108.

55. Anderson N, Heywood Everett S, Siddiqi N, Wright J, Meredith J et al. (2015) Faith-adapted psychological therapies for depression and anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 176: 183-196. [Crossref]